Drama manga can be among the most gripping stories, not because they rely on spectacle, but because they feel personal. At their best, they turn ordinary choices into turning points, then follow the fallout. The result is the kind of emotional momentum that pulls you through fast, then lingers afterward.

This list focuses on stories that earn their weight through character writing. Some titles lean grounded and realistic, built around relationships, work, ambition, and the quiet pressure of growing up. Others push deeper into shame, obsession, and psychological collapse, where the drama comes from who a character becomes when they can’t escape themselves.

These drama manga aren’t all the same, and this list reflects that range. You’ll find gentler, reflective reads like Omoide Emanon and I Had That Same Dream Again, alongside sharper, more adult stories like Utsubora and Helter Skelter. And you’ll also see darker character studies like Blood on the Tracks and Oyasumi Punpun, where the drama feels like a slow suffocation rather than a single breaking point.

A few standouts that define the list’s tone include Nana for messy relationship drama you can’t look away from, Solanin for post-college ennui, Blue Period for creative obsession, and A Silent Voice for guilt and redemption. On the heavier side, Freesia and Bokurano use high-concept premises to frame intimate tragedies, while Bokutachi ga Yarimashita turns one reckless choice into moral collapse.

What these series have in common is this: they take emotions seriously. Whether the story is quiet or chaotic, romantic or cruel, each one shows how identity and relationships warp under pressure, and how hard it is to undo the things you’ve said, done, or become.

Mild spoiler warning: I avoid major plot revelations, but I do reference themes and key moments to explain why each series belongs here.

With that said, here’s my ranking of the best drama manga (last updated: January 2026).

18. Omoide Emanon

Some drama manga don’t hit you with big speeches or tear-jerking moments. They work in a quieter register, where mood does most of the heavy lifting, and the emotional afterimage is the point. Omoide Emanon is one of the clearest examples of that kind of storytelling. It’s brief, restrained, and strangely unforgettable.

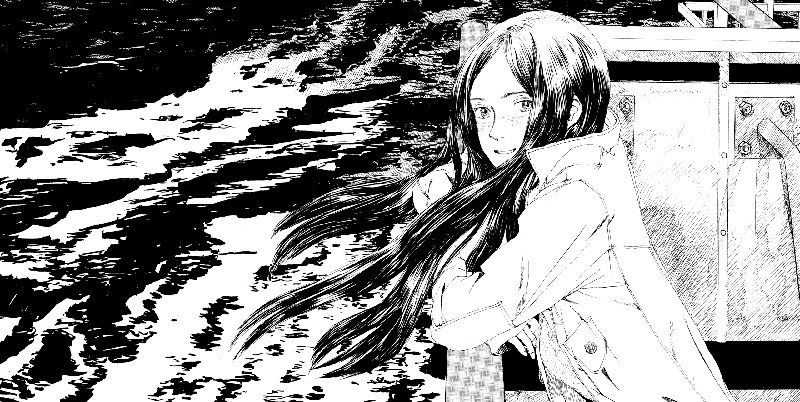

The premise centers on a young man who’s returning home after traveling, and on a ferry he meets a striking young woman who calls herself Emanon. They share a meal and start talking. What initially feels like a chance encounter with a faintly star-crossed vibe, slowly becomes something else. The conversation deepens, and the story takes on a more solemn shape, less like romance and more like being pulled into an extraordinary confession that you don’t know what to make of.

That’s the real appeal here. This is a drama manga built on longing and atmosphere, not melodrama. The ferry setting matters. The gentle motion, the sense of transit, and the feeling of life turning back toward home all reinforce the same undertone. Emanon herself carries that melancholy, too. She’s charismatic and warm, but there’s also something distant about her, almost ominous. By the end, what lingers is not a neat emotional resolution, but the feeling of having experienced something unique and rare, then being left alone with it.

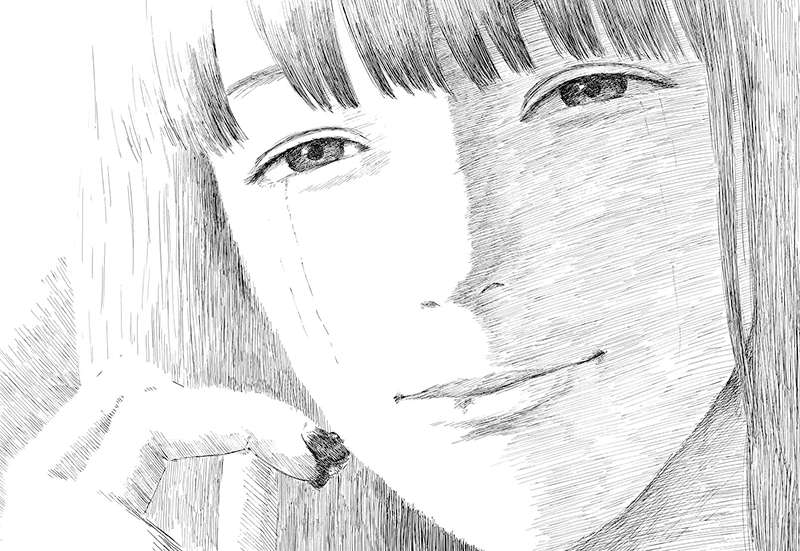

These feelings are amplified by Kenji Tsuruta’s art. The characters are rendered with realistic detail, and the environments feel alive without calling attention to themselves. Facial expressions do a lot of quiet work, especially in the pauses between lines of dialogue. Emanon’s presence is particularly well handled, both alluring and slightly unreal, which keeps the tone balanced between intimacy and mystery.

Omoide Emanon is a drama manga that’s reflective, melancholic, and more interested in mood than plot escalation, which makes it an easy recommendation.

Genres: Drama, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

17. Ikigami

Ikigami works as dystopian fiction first, but it earns its place on a drama list because the cruelty is always personal. The premise is brutally simple. A government program randomly selects citizens between the ages of 18 and 24 to die for the stability of the nation, and they receive their notice exactly twenty-four hours beforehand. It’s a horrifying concept, but the real chill comes from how ordinary it feels. This is state murder as policy, wrapped in procedure, and accepted as normal.

The framework is bleak, but the series shines in its vignettes. Each chapter follows someone through their final day and lets the drama unfold in full, messy range. Some characters try to reconcile with old friends and family they’ve neglected for years. Others lash out, spiral, or get consumed by despair. A few decide to make the day count in ways that are unexpectedly tender. Even when the story tilts toward hope, it still carries an aftertaste of grief, because the clock never stops ticking. The best moments have a sad beauty to them, not because the manga romanticizes death, but because it shows how much people reveal when they no longer have the time to perform.

Ikigami also focuses on the social fallout. Once someone’s received their Ikigami, the world changes around them. Friends keep their distance. Employers treat them like an inconvenience. Family members sometimes react with selfishness or panic, and not always in the ways you want. The most unsettling moments aren’t always the breakdowns. They’re the ones where everyone behaves as if this system is simply part of life, as if moral outrage is childish, and resignation is maturity.

Kengo Fujimoto, the messenger who delivers the Ikigami notices, ties the whole structure together. He’s not framed as a savior, and the story doesn’t let him become one. He’s a cog in a machine he increasingly distrusts, forced to witness raw human consequences while doing his job. That tension gives the broader setup its own dramatic spin, even when the focus stays on the recipients.

As a drama manga about institutional cruelty with a focus on human response, Ikigami is one of the sharpest.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Dystopian

Status: Completed (Seinen)

16. Solanin

Solanin captures a slice of early adulthood that a lot of manga rarely touch on. It’s not about chasing a grand goal or surviving a dramatic crisis. It’s about the slow pressure of ordinary life, the way days turn repetitive, and the quiet fear that your best years are slipping into routine. Asano frames it with a light touch, but the emotional core is heavy because it’s built from familiar disappointment.

At its center is the relationship between Meiko and Taneda, a young couple straight out of college, working low-paying jobs, clinging to small dreams, and trying not to admit how uncertain everything feels. When Meiko quits her job on impulse, it’s not treated as a triumphant break from the system. It’s treated like what it is: a desperate attempt to get your agency back. Eventually, their shared love of music becomes a lifeline, not because it magically fixes anything, but because it gives hope a place to exist.

Solanin is a drama manga driven by mood. It pays attention to what people say when they’re tired, what they avoid saying, and how easily love turns into quiet resentment when money, time, and insecurity take center stage. The tension is not explosive. It’s the constant, low-grade anxiety of growing up, the feeling that you’re supposed to want or do something, and the shame of not knowing what it is.

Asano’s art is a huge part of why it works. His cityscapes feel alive, and his paneling lingers on routines but never makes them feel empty. Faces carry exhaustion and tenderness in equal measure, and the story often lets silence do the talking. That restraint gives the harder emotional turns their force. When grief enters the picture, the manga treats loss as something that sits beside daily life and changes the feel of everything.

What separates Solanin from many similarly grounded stories is its final note. It hurts, and it stays sad, but it’s also Asano at his most hopeful. The message isn’t that dreams come true. It’s that life keeps moving, even if nothing changes like you hoped, and there’s something quietly beautiful in learning how to move with it.

Genres: Drama, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

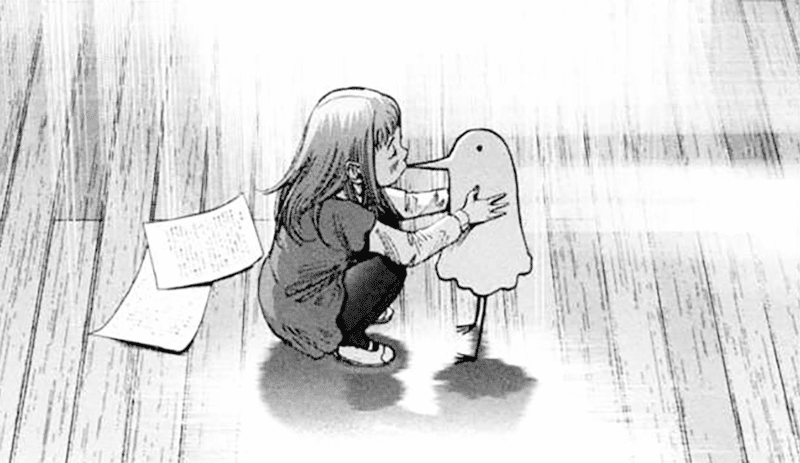

15. I Had That Same Dream Again

I found I Had That Same Dream Again by accident, and it hooked me almost immediately. On the surface, it’s a simple story centered on an assignment. An elementary school student named Nanoka is told to define what happiness means, and she treats the question with the same literal, defensive mindset she brings to everything. She’s prickly, self-protective, and quick to label herself as weird when she doesn’t want to engage with others.

It works because of who Nanoka meets while she’s trying to solve the assignment. Her life intersects with three very different people, each carrying their own private pain. There’s a cheerful woman who helps her save a cat, an elderly lady living quietly in the woods, and a high school girl Nanoka encounters at a moment that’s genuinely unsettling.

The story doesn’t turn those meetings into neat life lessons. Instead, it lets them accumulate before slowly hinting at what the story is really about.

This is a drama manga with a faintly whimsical structure. The conversations can feel a little storybook-like at first, as if you’re guided toward a message. If you don’t like sentimentality, you might bounce off it quickly. Still, that gentle tone is part of its charm because it makes the harder material easier to approach. Underneath the somber surface are touching themes like grief, loneliness, self-harm, and the long shadow of personal trauma. It’s not dark in the same way as the heavier entries here, but it’s quietly melancholic, and it knows how to land an emotional beat without turning it into spectacle.

The art is crisp, clean, and readable, which keeps the focus on expressions and small mood shifts. And once the narrative reveals how these encounters connect, the earlier weirdness feels purposeful rather than random.

If you want a drama manga that’s sad, reflective, and ultimately hopeful, I Had That Same Dream Again is an easy recommendation, especially if you’re in the mood for something tender.

Genres: Drama, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

14. Utsubora: The Story of a Novelist

Utsubora: The Story of a Novelist is framed like a literary mystery, but it lands because it’s really a character study about creative decay and the collapse of identity. It’s one of those drama manga series where the plot beats matter less than the emotional ugliness underneath them. Nakamura isn’t interested in romanticizing the artist. She treats writing as pressure that amplifies insecurity, envy, and longing until a person can’t tell the difference between craft and identity.

The setup follows a novelist past his peak. Shun Mizorogi’s public attention is fading, and the relationship to his work feels less like pride and more like dependency. Then a young woman, Aki Fujino, enters his life and dies soon after. The story doesn’t treat it as melodrama but as an intrusion that exposes the fragility of Mizorogi’s self-control. When her twin sister, Sakura Miki, introduces herself to him, the series turns colder. Around the same time, Mizorogi’s newest work becomes the center of a plagiarism scandal. Authorship, imitation, and self-preservation become the real conflicts, and Mizorogi’s choices reveal who he is long before the plot confirms anything.

What makes it work as a drama manga is how thoroughly damaged everyone feels, but in a quiet, believable way. Mizorogi is afraid of losing his relevance and becoming ordinary, but he’s also ashamed of needing praise to feel alive.

Aki’s death hangs over the narrative like a moral accusation. Sakura, meanwhile, adds a sharper edge to it. The manga never slows down to explain any of this. It lets them surface through behavior, deflection, and manipulation.

Asumiko Nakamura’s linework is restrained but delicate, and faces often show an eerie calm even during emotionally charged moments. Eroticism feels cold and disconnected, less about pleasure and more about control. That restraint makes the story’s bleakness linger.

Utsubora: The Story of a Novelist succeeds as a dark, melancholic drama manga, using an intriguing mystery framing to expose artistic death and identity erosion.

Genres: Drama, Mystery, Psychological

Status: Completed (Josei)

13. Aku no Hana

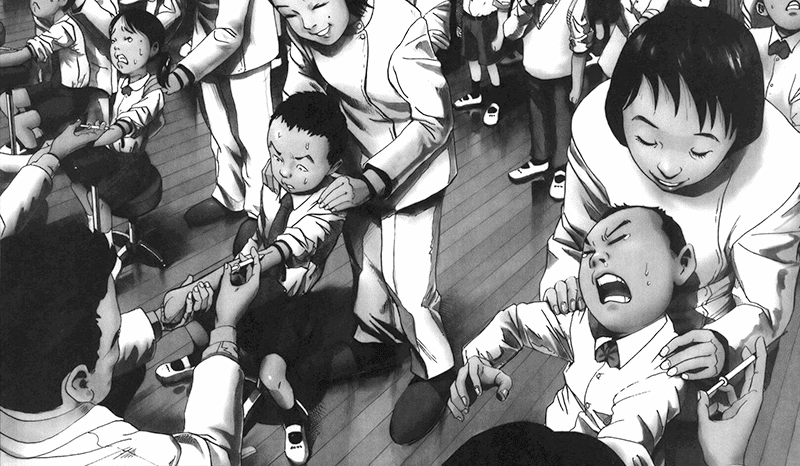

Aku no Hana turns adolescence into the stage for a deeply psychological drama. It’s set in an ordinary town, with a normal middle school and plain classrooms, yet it feels suffocating in the way few coming-of-age stories manage. The drama doesn’t come from a grand tragedy. It comes from humiliation, exposure, and the sense that one impulsive choice can stain the person you thought you were forever.

Takao Kasuga is a kid who pretends to be sensitive and refined, but he’s quietly afraid that everyone notices how insecure he really is. That fear becomes the foundation for what follows. When his classmate Sawa Nakamura witnesses him committing a petty theft, she uses it to blackmail him. It doesn’t work because he’s afraid of being punished, but because it touches the softest part of his identity, his need to maintain the fragile self-image he built, and his need to be seen as normal.

That’s what makes this drama manga so effective. Nakamura treats transgression as a way to free herself, but in reality it’s just another form of captivity. Through her demands, she creates a private world where shame is not only punishment but a reason to belong. Meanwhile, Kasuga’s obsession with Saeki shows his desperate need for normalcy. Yet the more he chases her approval, the more obvious it becomes that he can’t undo what he did. Everyone in this manga is wearing masks, and Oshimi is ruthless about tearing them down.

The character writing keeps the series from feeling like a cheap provocation. Kasuga isn’t the victim he first appears to be, while Nakamura is much more than a deranged psychopath. They’re teenagers, full of raw emotions, and acting out of loneliness, resentment, boredom, and a hunger for meaning. The manga’s first half escalates in ways that can feel outrageous, but it also captures a truth about teenage logic. When you’re at that age, ordinary spaces start to feel suffocating, and even the smallest act can take on an unfathomable weight.

Oshimi’s art amplifies those feelings with vulnerable faces and heavy silences. The town feels exposed, as if rumors are spreading and everyone’s quietly judging.

The manga’s later chapters take a step back from the earlier, more outrageous escalation and instead shift into consequence and reflection. It’s less interested in shock than in what comes after. If you want a drama manga that’s emotionally punishing early on, but ultimately more hopeful than its reputation implies, Aku no Hana is among Oshimi’s most distinctive works.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Coming-of-Age

Status: Completed (Shonen)

12. Onani Master Kurosawa

Some people will see a title like Onani Master Kurosawa (literally Masturbation Master Kurosawa) and assume it’s either a raunchy gag manga or an edgy adult-themed work. That’s exactly why it works so well as a subversion. Beneath the provocative title lies one of the most tender coming-of-age stories and memorable drama manga I’ve ever read.

Kakeru Kurosawa is a fourteen-year-old loner with a superiority complex and a private habit he treats like a ritual, sneaking into a rarely used school bathroom every afternoon. He looks down on his classmates, confuses cynicism with intelligence, and hides behind his arrogance. When his classmate Aya Kitahara gets bullied, he decides on revenge in the most warped way he can. Then Kitahara discovers the truth, but instead of turning him in, she blackmails him into continuing. What starts as perverse vigilantism turns into a loop of guilt, shame, and escalating consequences.

The early chapters read like a crude parody of Death Note, with a self-important kid acting like a scheming mastermind. The impressive part is how gradually the series pivots. It stops caring about the deeds and focuses on what happens to a person who keeps rationalizing their worst impulses. Kurosawa isn’t treated as a misunderstood victim, and the story doesn’t rush his growth. It forces him to sit down, recognize his own ugliness, confront the damage he’s caused, and learn how to connect with people without judging them. Kitahara’s role deepens, too. She isn’t just a plot device but a character with her own fears, pride, and vulnerability.

The art supports that shift. Expressions carry the emotional load, the shading feels raw, and any sexual material is framed as unsettling rather than exploitative. That restraint lets the later chapters land as something genuinely heartfelt, even quietly inspiring, without pretending the early harm never happened.

I first read Onani Master Kurosawa almost two decades ago, and it still sticks with me. It’s a drama manga that takes an outrageous setup and turns it into a story about mistakes, accountability, and first love.

Genres: Drama, Coming-of-Age

Status: Completed (Seinen)

11. Nana

Nana looks deceptively simple at first. Two young women with the same name move to Tokyo, become roommates, and stumble into adulthood with the music industry as the backdrop. The early arcs can make it feel like a stylish slice-of-life romance with industry flavor. The longer you read, however, the clearer it becomes that this is one of manga’s most intimate relationship dramas, and one of the most emotionally draining reads in manga.

The two leads couldn’t be more different. Nana Osaki is a punk vocalist with a hard edge and a clear dream, the kind of person who turns pain into ambition and treats vulnerability like a weakness. Nana Komatsu, nicknamed Hachi, is a romantic drifter who wants love so badly she keeps mistaking longing for stability. Their friendship is the emotional center of the story, not because it’s wholesome, but because it’s honest. They need each other, they misunderstand each other, they hurt each other, but keep circling back the way real bonds do.

What makes Nana such a standout drama manga is how little it romanticizes its characters. Ai Yazawa writes people who are messy, impulsive, and sometimes selfish, but never fake. Everyone carries baggage. Everyone wants something that’s not easily available. The series explores cheating, codependency, addiction, grief, depression, and the slow erosion that sets in when love turns into a coping mechanism instead of a connection. The music industry element adds pressure and glamor, but the story’s real weight is domestic and emotional. It’s about the choices people make when they’re afraid, and the way those choices become identity.

Yazawa’s art is a huge part of the appeal. It’s elegant and sophisticated, making the emotional highs feel earned, and the lows quietly devastating. Somber scenes hit hard because the faces and body language are so expressive. You can tell when someone’s lying, and you can feel when they’re lying to themselves.

I first discovered Nana through its anime adaptation, and it still holds up as a fantastic entry point, but the manga goes further. It’s longer, more detailed, and ultimately darker. Even with its long hiatus, it’s a strong pick for fans of drama manga that treat love as something beautiful, destructive, and painfully human.

Genres: Drama, Romance, Psychological

Status: On Hiatus (Josei)

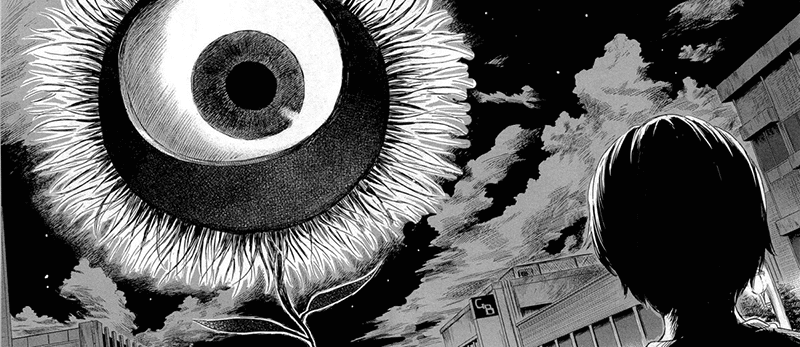

10. Nijigahara Holograph

Nijigahara Holograph is notorious for being confusing, but that fractured structure is more than a gimmick and not there simply to make the story feel clever. It mirrors what the manga is actually about: trauma that doesn’t resolve cleanly, guilt that never fully leaves, and lives that keep circling back to the same damage from different angles. This is a drama manga where time feels less like a straight line and more like a loop.

In a small town, a quiet act of childhood cruelty turns into a haunting shadow that stretches across years, shaping relationships even when characters pretend they’ve moved on. What makes it feel suffocating is the ripple effect. Trauma doesn’t stay contained, but spreads outward, changing friendships, altering self-image, and shaping how people hurt others and themselves. There’s a generational undertone: parents who damage their kids without noticing, authority figures who normalize cruelty, and kids who inherit that violence and carry it forward.

Asano’s narrative is deliberately fragmented to reinforce those themes. Different viewpoints blur into one another, and scenes jump between timelines. It turns the manga into a puzzle of fragments, where cause and effect arrive out of order, and character motivations remain hidden. But even when the pieces finally click, there’s no relief. Understanding doesn’t redeem those characters. It only clarifies how trapped they are in patterns they can’t break, even when those patterns turn self-destructive.

It’s also one of the bleakest entries on this list. Atrocities are front and center, not as isolated shocks, but as symptoms of a world that’s cold and casually cruel. The setting looks ordinary, but it’s that seeming normalcy that makes it worse. Asano’s grounded and precise art makes people look like real people, streets like real streets, and the ugliness hits harder because nothing about the presentation suggests distance or fantasy.

That said, the manga isn’t uniformly hopeless. There are brief moments of tenderness, and a few characters reach toward something better. Others spiral into toxic relationships, or end in ways that feel brutally final. Nijigahara Holograph will frustrate readers who want clean answers or tidy timelines, but if you’re open to ambiguity and rereading, it’s one of the most devastating drama manga ever written. It’s not just about what happened. It’s about how long it keeps happening inside people.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Mystery, Surreal

Status: Completed (Seinen)

9. Bokurano

Bokurano might look like an odd fit on a drama list at first. It’s a science-fiction mecha manga about middle schoolers piloting a giant robot to protect the world. That premise usually comes with spectacle, wish fulfillment, and heroic arcs. Bokurano takes the opposite route. It uses the robot as a trap and builds a narrative about the cost of stepping into it.

The premise centers on a group of kids who stumble into a supposed game, agree to it, and only afterward learn what the agreement actually means. Each battle becomes a countdown. Heroism doesn’t remove the damage, and saving the world is neither clear nor glorious. Cities are leveled, people die, and the kids have to live with the fact that even victory doesn’t spare them. That’s where the drama comes from. The manga keeps asking what to do with your remaining time when you’re expected to die to save the world.

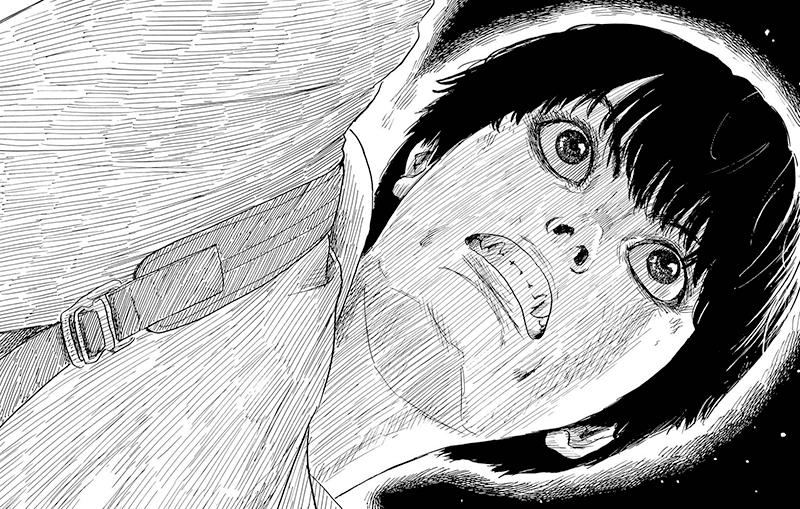

Bokurano is less a conventional narrative and more a chain of character studies, shifting from child to child, each with their own emotional backstory. Some spiral and lash out, some detach, and some search for meaning. The darkness isn’t confined to the cockpit either. Several children suffer from trauma shaped by toxic families, abuse, and exploitation. All of this makes the premise hit harder because it doesn’t play like a science-fiction epic.

I first encountered Bokurano through its anime adaptation, but it’s the manga version that fully commits to the bleakness. It leans hard into the uglier sides of the story and is more willing to show rather than hint at the darker themes. That said, Bokurano is a divisive series. It’s full of clunky philosophical interludes, characters who don’t act or talk like kids, plus a deadpan tone that can be jarring. For others, the emotional numbness is the point, showing the kids’ reaction to a situation too large for them to process.

Bokurano is a story that will stay in your mind. It’s less interested in saving the world and more in showing the cost, and how little comfort anyone gets in return. It’s a bleak drama manga that’s fatalistic, nasty, and focused on psychological erosion rather than catharsis.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Sci-Fi

Status: Completed (Seinen)

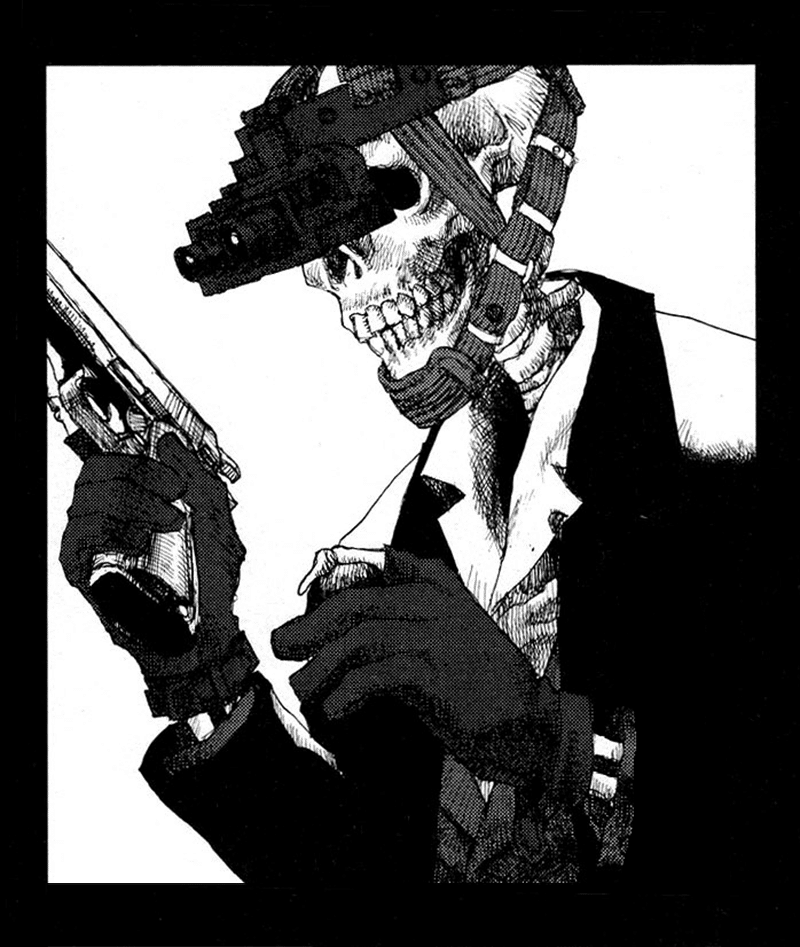

8. Freesia

Freesia is an odd fit if you expect drama to center on domestic realism or relationships. On the surface, it reads like a revenge thriller set in a near-future Japan that has legalized retaliation. If someone is murdered, the victim’s relatives are given the right to kill the offender, either by themselves or by hiring enforcers to do it for them. It sounds like justice, but the series treats it as something closer to institutionalized rot, a society turning its worst instincts into procedure.

Kano is one such enforcer, tasked with finding and killing people whose names have been approved for retaliation. Early on, the premise could’ve been played as catharsis, but Matsumoto never lets it become satisfying. The retaliations aren’t normal payoffs. They’re purely administrative. This is where Freesia becomes a drama manga. The emotional core isn’t the action but the consequences, and the way violence reshapes everyone involved.

The manga’s most distinctive choice is showcasing the inner workings of Kano’s mind. His delusions and hallucinations are constant and intrusive, bleeding into everything until he’s not sure anymore what’s real and what isn’t. Instead of giving you a safe, objective distance, the manga forces you to suffer through those episodes alongside Kano, which makes even the most mundane moments feel dangerous and wrong. Kano’s private life adds another layer of quiet tragedy. He’s a broken man trying to function, living with an elderly, demented mother, clinging to the idea of normalcy, and trying to maintain relationships without fully realizing how broken they are.

Around him, nearly everyone else feels damaged or numb. The retaliation law is supposed to bring justice, but only serves to multiply loss. Targets might be remorseful or products of the same brutal society that now condemns them, but none of that matters. It’s simply procedure, where guilt and innocence don’t matter.

The enforcers might even be more warped than the targets. Freesia is blunt about how this type of work burns empathy and leaves nothing but ugliness behind. Matsumoto’s art supports that bleakness. It’s gritty and claustrophobic, with a thin boundary between realism and surreal intrusions. When the manga leans into sexual themes or depictions of violence, it’s never exciting but grotesque, reinforcing how deep the world has fallen into darkness.

As a drama manga, Freesia is one of the harshest and most memorable examples of societal decay explored through the psychological collapse of its characters.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Crime

Status: Completed (Seinen)

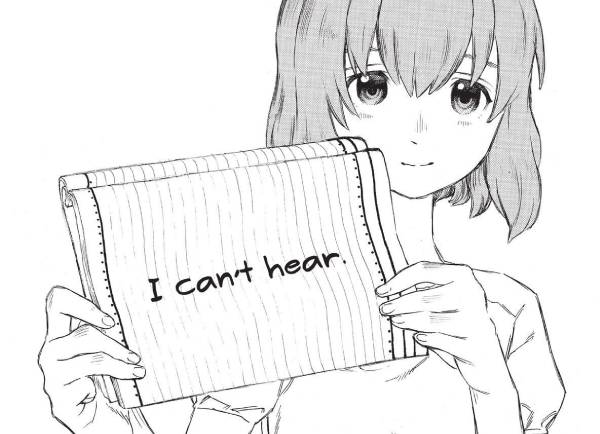

7. A Silent Voice

A Silent Voice starts in the one place most redemption stories avoid. Shouya Ishida isn’t introduced as misunderstood or misguided. He’s a bored kid who turns cruelty into entertainment when Shouko Nishimiya, a deaf girl, transfers into his class. What begins as teasing turns into bullying, and the manga isn’t shy about showing how ugly it gets. Teachers fail, classmates participate or stay quiet, and Shouko is forced to suffer through it until she leaves. Then the social order flips, and the class finds it convenient to pin everything on Shouya. The bully becomes the new target.

These early stretches can be a tough read, but they earn what comes next. We see Shouya years later, now in high school, isolated and steeped in self-loathing. He eventually decides to find Shouko and apologize, and this is where the series reveals its true subject. It’s not a story about bullying. It’s a drama manga about atonement, how messy and awkward it can be, and how saying sorry doesn’t undo what you did.

The reconnection is handled with restraint. Shouya doesn’t become a better person overnight. He’s anxious, defensive, and terrified of being rejected, and often behaves like someone trying to earn forgiveness rather than understand what forgiveness actually means. Shouko isn’t written as a saint either. She wants connection, but she’s also shaped by what happened, and her responses carry hesitation and contradiction. That complexity makes the relationship feel real instead of like pure wish fulfillment.

The supporting cast deepens the moral mess. Old classmates resurface with their own version of how the bullying went down, and the story shows how people rewrite the past to protect themselves. Some characters are sympathetic one moment and infuriating the next, which is exactly the point. Harm is communal, and denial is, too.

Ōima’s art matches the tone. It’s clean and understated, but pays close attention to posture, expressions, and small gestures, which matters because of Shouko’s deafness. Many panels linger on quiet moments, and silence itself becomes part of the emotional experience rather than empty space.

Not every plot thread gets equal closure, and the ending may feel abrupt if you want a neat resolution. Still, A Silent Voice is one of the most affecting modern coming-of-age stories because it refuses easy redemption. It’s a drama manga about consequences, empathy, and the fragile hope of rebuilding trust.

Genres: Drama, Romance, Slice of Life, Psychological

Status: Completed (Shonen)

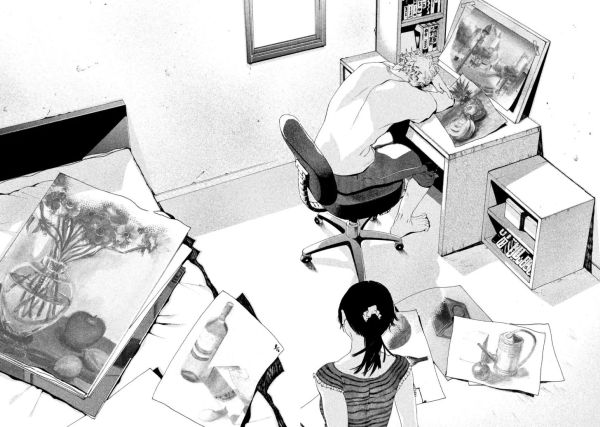

6. Blue Period

Blue Period is the kind of story that proves drama doesn’t need romance, tragedy, or betrayal to hit hard. Its tension comes from something quieter and more familiar: the slow panic of realizing you’re living on autopilot, then chasing a dream with everything you can, only to realize you might not be good enough. It’s a drama manga built around effort, identity, and the discomfort of starting from zero.

Yatora Yaguchi looks fine from the outside. He gets good grades, has friends, and knows how to play the role of a functional teenager. The problem is that none of it feels real to him. The numbness shifts when he notices a painting that awakens something in him he can’t explain. From there, the series doesn’t focus on a magical awakening, but on a decision to commit. Yatora dives into fine art with the desperation usually reserved for people trying to save themselves.

What makes Blue Period stand out is how unromantic it is about creativity. It treats art as a craft, meaning progress comes through mistakes, studies, ugly early attempts, and the slow work of developing an eye. The manga focuses heavily on process, and it’s honest about the emotional toll it takes. Envy, self-doubt, impostor syndrome, and the constant fear of wasting time all show up, not as dramatic twists, but as daily pressure. One of the series’ most memorable ideas is that you don’t need to be a genius if you’re willing to work until no one can tell the difference anymore. It’s a very specific mindset, but it captures the story’s core tension. How badly do you want to succeed, and what are you willing to sacrifice to earn it?

The supporting cast deepens that question. Each character reflects a different relationship to art, talent, privilege, insecurity, and expectations, which keeps the narrative from turning into a single-perspective, motivational arc. The struggles aren’t interchangeable artist problems, either. They feel personal, and sometimes ugly in ways that fit adolescence and ambition.

Visually, Yamaguchi balances expressive faces with dense, technique-heavy pages, but the clarity stays intact. The art keeps the focus on what matters: a person changing under pressure. Blue Period stands apart among modern drama manga for treating creative pursuit as both a lifeline and a grind.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Slice of Life

Status: Ongoing (Seinen)

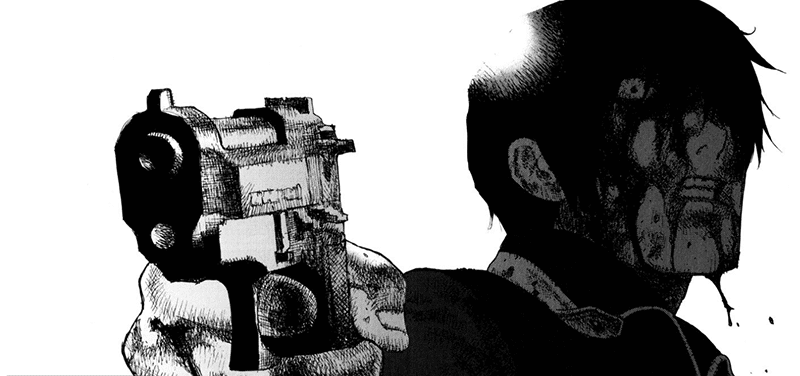

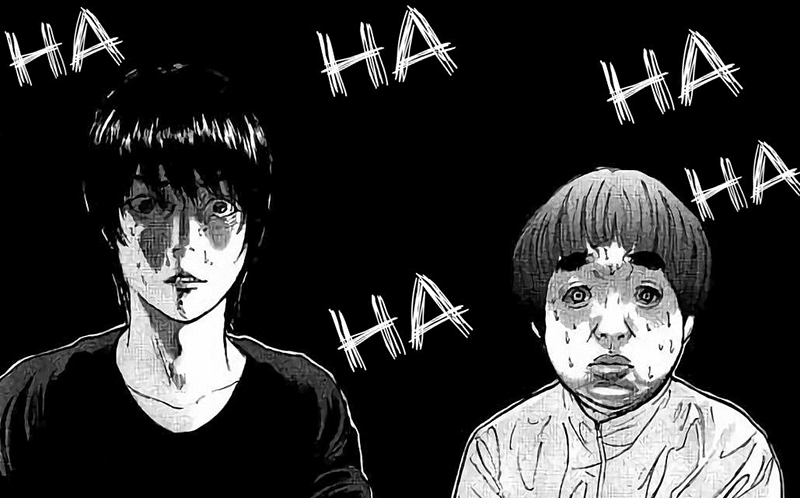

5. Blood on the Tracks

Blood on the Tracks is proof that most frightening stories don’t need monsters. Shūzō Oshimi builds a drama around a single relationship, a tight bond between a mother and son that makes love, dependence, and fear inseparable. It can read like psychological horror, but the core is domestic. The terror comes from how ordinary the setting is and how plausible the emotional control feels.

Seiichi Osabe, a quiet middle-schooler, lives under the watchful eye of his mother, Seiko. At first, she appears affectionate, devoted, and overprotective in a way that feels almost normal. It’s a reminder of how care and possession can blur. All that changes during a family trip when Seiko does something so shocking it changes their entire dynamic. Seiichi becomes trapped and unable to explain what he witnessed to anyone. This turns the manga into a study of emotional captivity. Here, the worst punishment isn’t physical, but the rewriting of a child’s inner life.

Blood on the Tracks stands out for its pacing. Oshimi doesn’t rely on dialogue, but instead stretches simple moments until they become unbearable, letting heavy silences do the talking. Chapters may center on a single, harrowing expression. This doesn’t just make you understand Seiichi’s paralysis but share it. All this is reinforced by the art. The framing is tight. Close-ups of Seiko’s face dominate the page, and backgrounds fade. The meaning is instantly clear: the real danger is the person closest to you. Even when nothing happens, the atmosphere tightens, tension spikes, as if the unspoken is more terrifying than any action.

As a drama manga, Blood on the Tracks succeeds because it turns something foundational into something horrific. A parent is supposed to be the constant in a child’s world, the one place you can retreat to and feel safe. Oshimi corrupts that bond, showing us the long-term damage of such an upbringing. Seiichi isn’t simply scared. He’s conditioned to second-guess reality, to apologize for his feelings, and to accept emotional distortion as normalcy.

The final stretch deepens the tragedy by shifting into Seiichi’s later years, which shows that the entire experience doesn’t simply end because childhood ended. It also reframes Seiko. She’s not redeemed, but shown as someone who’s been broken long before she ever became a mother.

Blood on the Tracks is one of Oshimi’s most devastating works. It’s an intimate, controlled drama manga that’s emotionally brutal.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Horror, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

4. Helter Skelter

There are many manga that focus on showbiz, but Helter Skelter is among the darkest. A person is manufactured, polished, and sold, then discarded the moment she stops performing. Kyoko Okazaki doesn’t frame it as a tragic cautionary tale with a clean moral, but as a narrative that shows what happens when someone has been turned into an image long enough that no real self is left behind.

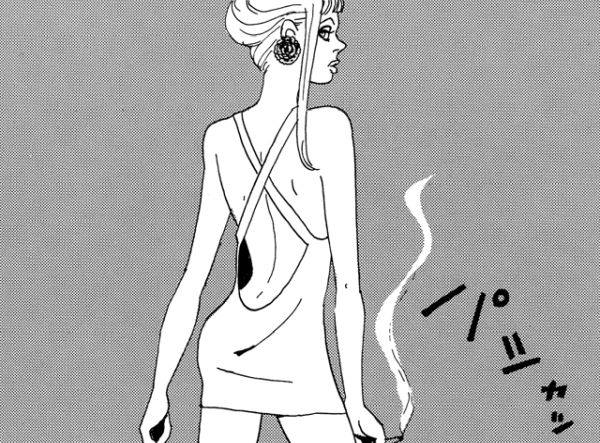

We get to know Liliko Hirokuma, Japan’s top model at the height of her career. Yet her perfection is a lie. Her body has been engineered through plastic surgery, and her public persona is sustained through constant monitoring, performance, and pressure to stay desirable. The story’s tension comes from deterioration, not a single scandal or downfall. When attention drifts toward younger faces, and her body begins to fail, her current lifestyle becomes impossible. The horror isn’t just losing fame, but that there’s no identity left once the spotlights turn away.

Okazaki never presents Liliko in a singular light, but depicts her as both predator and victim. She’s been shaped by obsession, exploitation, and an industry that rewards self-erasure. It’s her response to this that makes it worse. She turns fear into cruelty, following an ugly logic. If she’s being replaced, she’ll punish whoever’s been suggested as her replacement and take as many people down with her as she can. That’s where the drama sharpens, because it’s not insanity. It’s a symptom, a reaction to a system that trains people to treat themselves as a product.

The collateral damage is wide. Liliko’s assistant becomes entangled in a relationship built on manipulation, dependency, and substances. A young rival becomes a target, not because Liliko personally hates her, but because the industry decided she’s going to replace her. Even worse, the executives, photographers, and anyone else in the industry treat this with cold indifference. No one is shocked, no one cares. They’re only interested in money, and how long they can keep monetizing a product.

The manga’s raw and uneasy linework reinforces that instability. Faces look slightly off even in quieter moments. The art avoids glamor on purpose, constantly reminding us that the polished, perfect Liliko is a lie, and that what’s hidden beneath is coming apart.

Helter Skelter is an unforgettable drama manga that stands out for its depiction of showbiz as a horrifying culmination of vanity, image, and addiction.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Avant-Garde

Status: Completed (Josei)

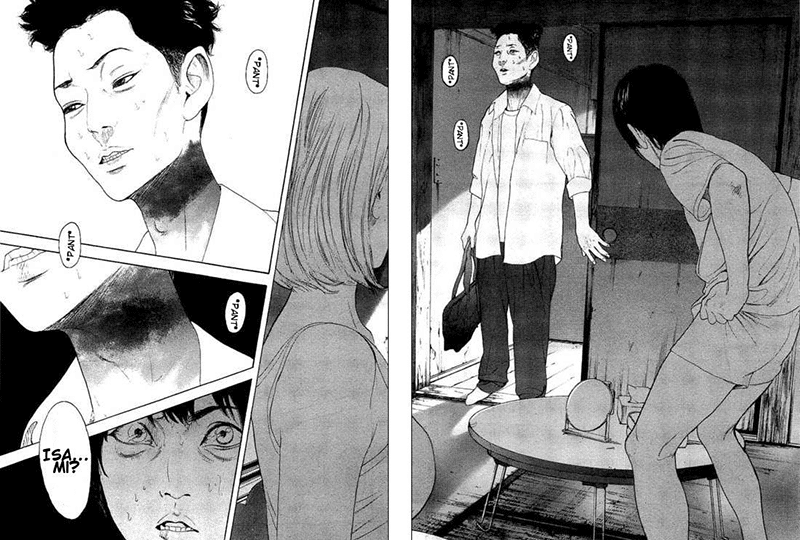

3. Inside Mari

Inside Mari starts with a premise that sounds like a cheap hook, then uses it to dig into something far more personal. A lonely college dropout wakes up in the body of a high school girl, and the story immediately raises the one question that matters: why and how did this happen?

Isao Komori is introduced as a shut-in. He’s withdrawn and has drifted into a routine of isolation, observation, and self-indulgence. His fixation on Mari begins as escapism, not romance. She represents the idea of normalcy he can’t seem to reach anymore. When the body swap occurs, it’s not framed as wish fulfillment. It plays like an invasion. Komori is dropped into a life he doesn’t understand, has to perform as Mari in public, and feels the constant friction between what he has to hide and what the world demands from him.

This is a drama manga disguised as a psychological mystery. The tension isn’t about solving the reason behind the body swap, but about identity buckling under pressure. Oshimi is interested in showing shame, repression, and dissociation, and uses them to depict scenes that are uncomfortable because they feel emotionally honest. Slowly, the story peels back its layers, and each new detail changes what came before, never through shock, but through accumulation.

Mari’s life becomes central to the narrative, reframing the premise without giving the reader easy answers. Family, school, and the roles people are forced to play matter as much as the mystery itself. Yori’s presence deepens the emotional core. She’s not merely there to help move the plot along, but brings her own baggage into the story. The relationship that forms around investigating the truth carries real dependency, distrust, and need.

Oshimi’s pacing is patient and controlled. Quiet moments, awkward pauses, and expressions that say more than dialogue ever could dominate the page. The clean linework and tight framing make ordinary streets and classrooms as oppressive as the idea of being trapped in a different body. That visual restraint keeps the story grounded even when the situation grows more unreal.

Inside Mari is the kind of manga where going in blind is part of the experience. If you want a drama manga that uses a strange setup to explore loneliness and identity, Inside Mari is a strong pick.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Mystery

Status: Completed (Seinen)

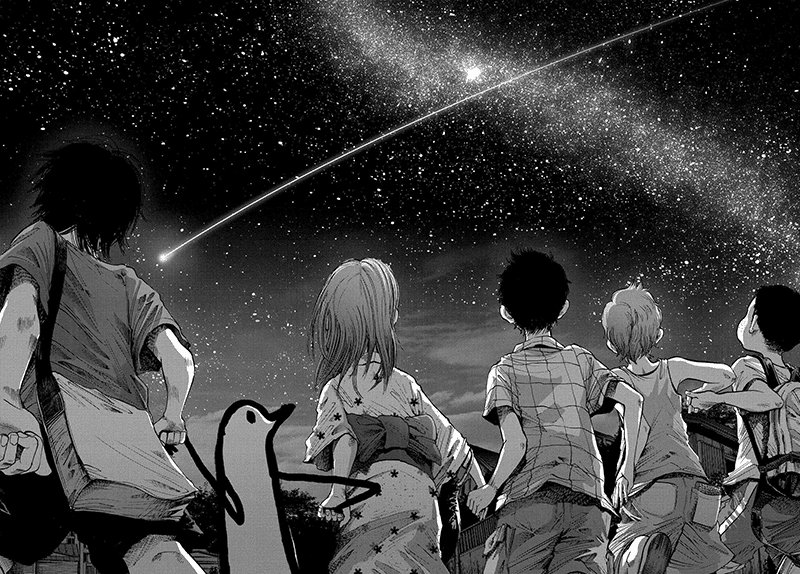

2. Oyasumi Punpun

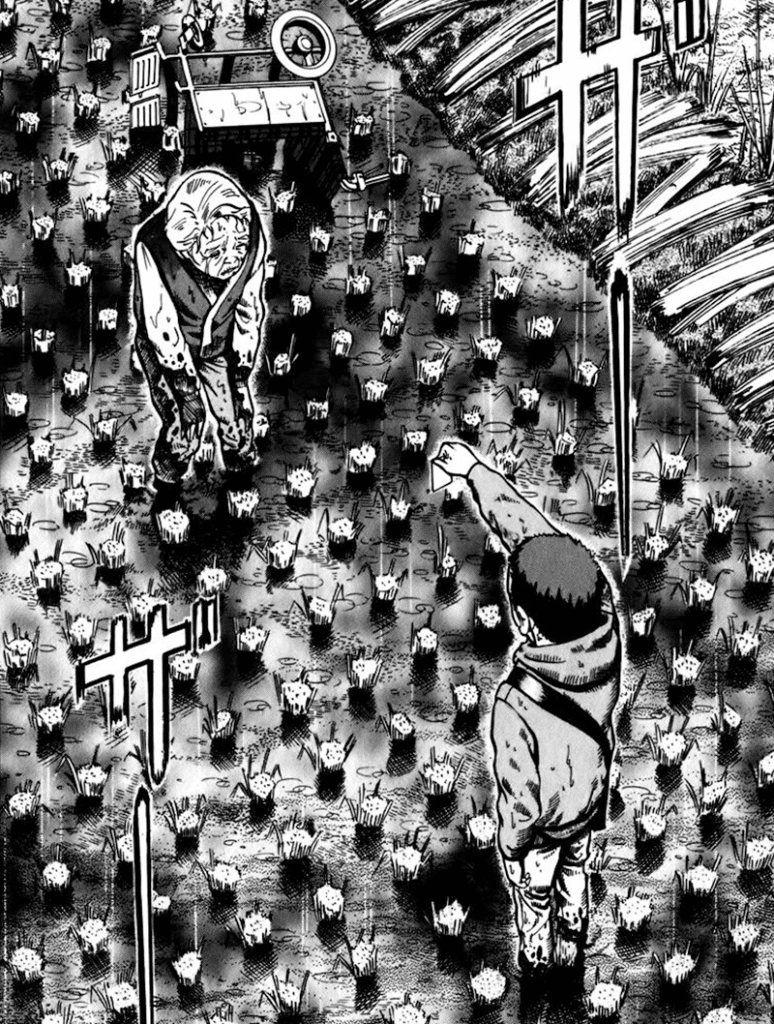

Oyasumi Punpun has a reputation that can almost feel mythic, as if it’s famous for being sad in a performative way. What makes it hit so hard is the opposite. Inio Asano doesn’t build devastation out of dramatic twists or constant catastrophe. He builds it out of erosion. This is a drama manga where life doesn’t collapse due to a single event, but warps a person over time through shame, neglect, and the echoes of early damage.

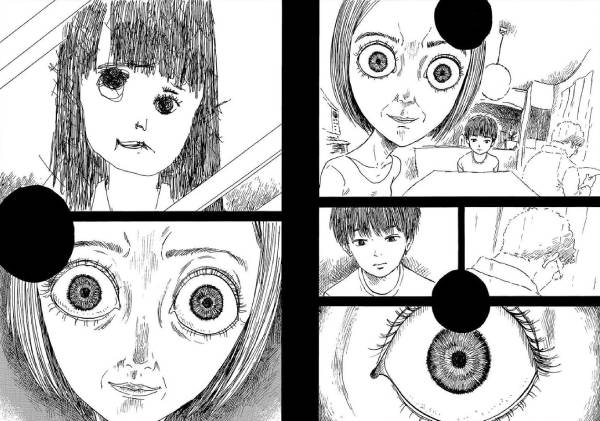

Punpun Onodera starts out as an ordinary child. He doesn’t have big dreams, just the same wants as any other child. This premise is the point. He’s not special or destined for tragedy. Instead, he shows how a child can be warped by broken adults, an unstable home, and relationships that bring more harm than relief. The early chapters feel deceptively quiet, but the accumulation is relentless. An awkward look, a harsh word, a moment of tenderness turned sour. Over time, those moments not only stack but corrupt.

What makes it all work is a singular visual decision. Asano renders Punpun and his family as caricatured bird figures, while his environments are drawn with intense realism. We see cramped apartments, harsh streets, and the oppressive texture of everyday life. This creates constant dissonance. Punpun doesn’t feel at home in his own story, but that distance makes his emotions more exposed. It’s almost as if the manga refuses to let him hide behind a human face, and lays everything bare for us to see.

The relationships are where the series becomes genuinely harrowing. Love rarely feels safe. Intimacy becomes tangled with dependency, jealousy, and desire. Many people long to be saved, but come to rely on those who need saving themselves. Characters are often both damaging and sympathetic, with Asano refusing to label or judge them. This ambiguity makes the story so draining because it’s exactly how real people act.

The manga’s later stretches swap slow suffocation for something louder and more chaotic. Yet as the story continues to escalate, it also starts feeling more melodramatic. Even then, it still fits the core theme. When depression turns outward, it becomes ugly, messy, and often irreversibly destructive.

Oyasumi Punpun is a drama manga that captures emotional collapse without romanticizing it. It’s one of the darkest stories in manga, not merely because it’s sad, but because it shows how low someone can fall, and despite everything they’ve done, life might just continue anyway.

Genres: Drama, Psychological

Status: Completed (Seinen)

1. Bokutachi ga Yarimashita

Bokutachi ga Yarimashita is one of the sharpest manga I’ve read about guilt as a long-term condition. It doesn’t treat wrongdoing as a simple dramatic event followed by punishment or redemption. It treats it as something that contaminates the rest of your life, even when everything on the surface looks normal again. The tension isn’t external danger. It’s the psychological aftermath.

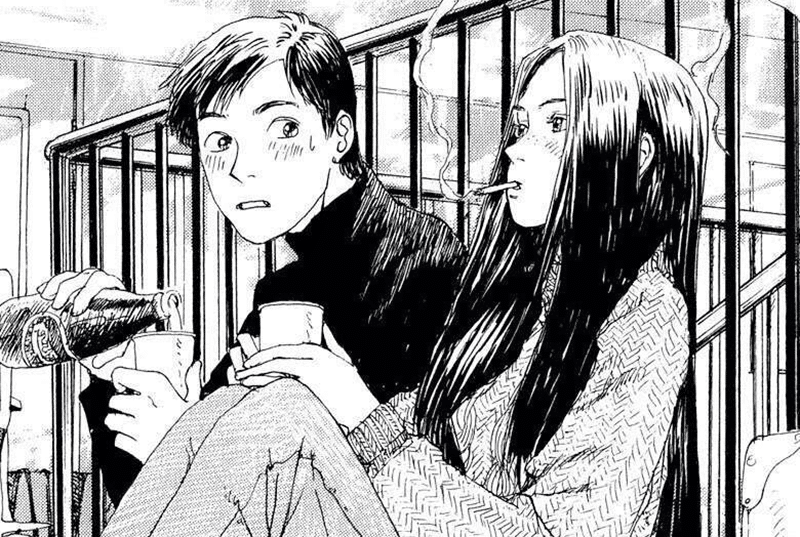

The manga follows Tobio Masubuchi and his friends, a group of teenagers who drift through school with a vague sense of boredom. They aren’t masterminds, and they aren’t hardened criminals. When they decide to get revenge against another school, it’s framed as an impulsive prank that feels satisfying in the moment. Then the situation escalates. The manga doesn’t bother with excuses and instead becomes an anatomy of what it means to live with a mistake you cannot undo.

Each of the friends copes in a different way, and that’s where the drama becomes intimate. One leans into denial and forced normalcy. Another chases distraction, sex, or opportunity, as if these things can drown out conscience. Others unravel quietly, trapped in paranoia and self-hatred, where even the most mundane interactions feel dangerous.

Instead of cheap melodrama, the manga focuses on shame. Many of the more pivotal scenes are built on what’s not said: the pause in conversation, the way friends avoid eye contact, or the forced normalcy because anything else would destroy the lie. All this is shown in the art. It’s not flashy, but it’s precise about facial expressions and body language people use to hide that they’re breaking apart.

What makes Bokutachi ga Yarimashita linger is its refusal to offer clean catharsis. There’s no redemption arc, and it doesn’t pretend that time heals. Years later, when everything seems normal again, the story insists on a harsh truth. Some damage never goes away. It becomes part of you, and the rest of your life is shaped by it.

Bokutachi ga Yarimashita is brutally human and stands apart as one of the sharpest drama manga for portraying consequences rather than spectacle.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Crime

Status: Completed (Seinen)