There’s no one as famous in the world of horror manga today as Junji Ito. He has rightfully amassed a global cult following.

Yet Ito is not merely a horror mangaka. He’s one of the greatest horror artists alive today. If you’re a fan of horror, especially horror manga, you’ve likely encountered his work.

Ito’s body of work is as strange as it is distinctive, and reading his manga feels like falling down a very particular rabbit hole.

His catalogue spans hundreds of pages of short fiction collected in English anthologies, as well as several longer works that showcase his skill at building uniquely unsettling worlds. Whether you start with a one-shot or a full volume, the same obsessions return: bodily transformations, cosmic horror, psychological collapse, and the corruption of the mundane.

In the sections below, I explore these elements, the signature techniques of his visual style, and his recurring narrative themes.

Discovering Junji Ito

I first learned about Junji Ito a decade and a half ago when I was searching online for new horror manga to read. At the time, I was still new to the genre, but the prospect of a manga that was supposed to “give me nightmares” sounded interesting enough.

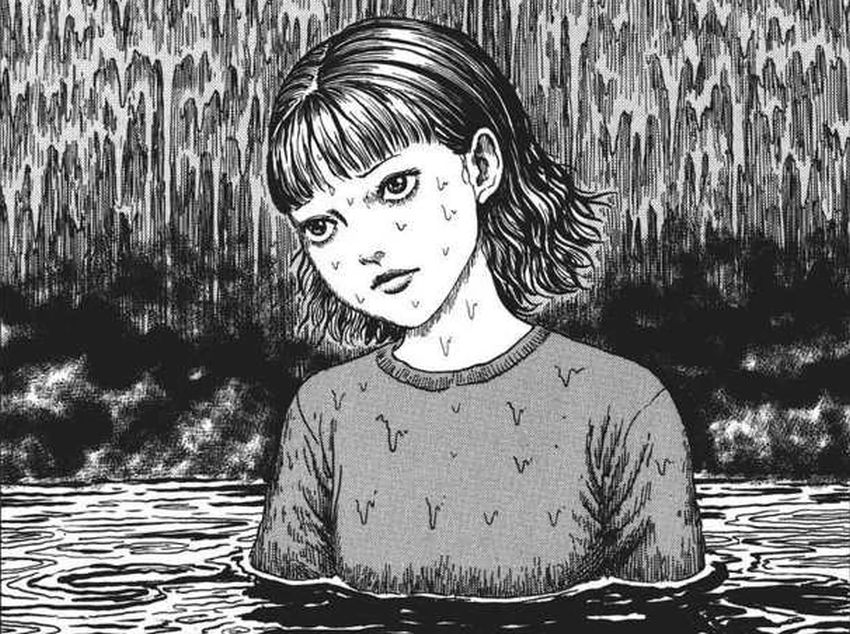

That manga was Tomie, and when I finally read it, it was everything I desired in a work of horror and much more. It was full of outlandish ideas and terrifying imagery.

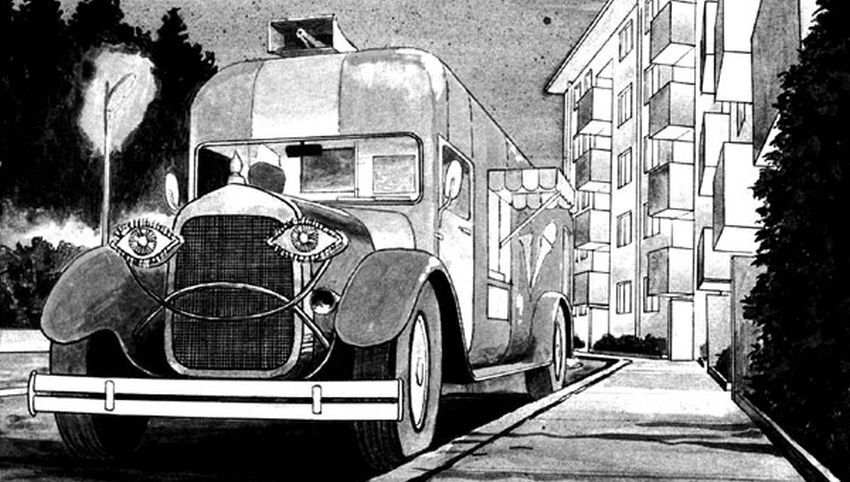

The next manga by Junji Ito I read was Gyo, which was as nightmarish as Tomie but much more surreal, weird, and absurd. His style was as fantastically disturbing and nightmarish as in Tomie.

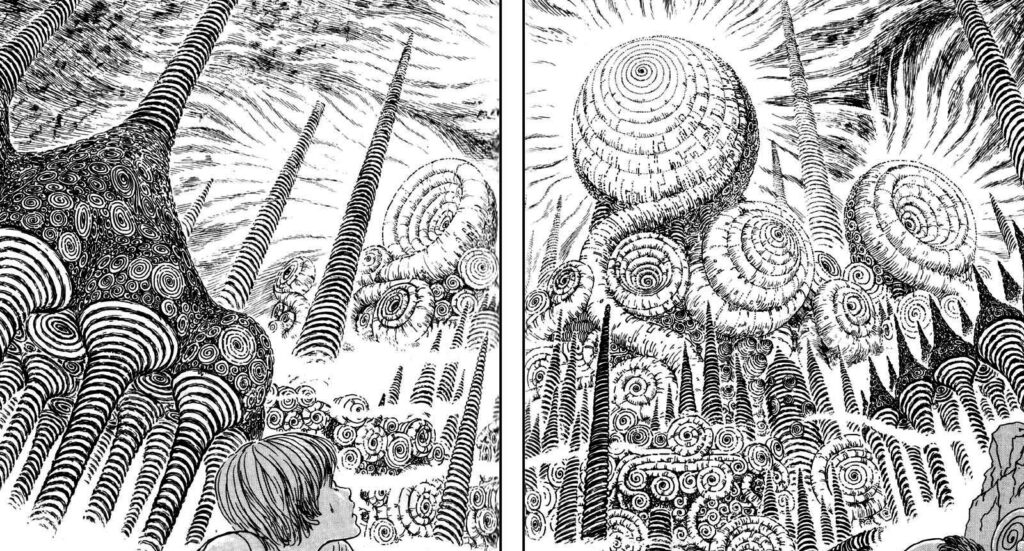

What finally sold me and made me a lifelong fan of his work was Junji Ito’s masterpiece, Uzumaki. It’s the story of the small coastal town of Kurouzu-cho, which is haunted by spirals. The story was outlandish, the imagery disturbing. It felt completely unique and was unlike any other horror manga I’d read until then. For readers curious about Uzumaki, I also put together a short article about my favorite Uzumaki chapters.

Over the years, I’ve read countless horror manga, both by well-known and lesser-known writers, as you can see in the list of my favorite horror manga. Still, Junji Ito’s works hold a special place in my heart and are, in my opinion, among the best horror manga of all time. His works are so strange, so unique, and so outlandish that I find myself going back to them time and again.

Junji Ito – Works and Style

What makes Junji Ito’s works so fantastic is his blend of outlandish, sometimes supernatural horror with the mundane.

Junji Ito’s work truly shines because it’s a very specific kind of horror. His stories seldom feature killers or monsters. Instead, his horror is often unexplained, comes from powers outside our influence, or arises from our own faults, fears, obsessions, and phobias.

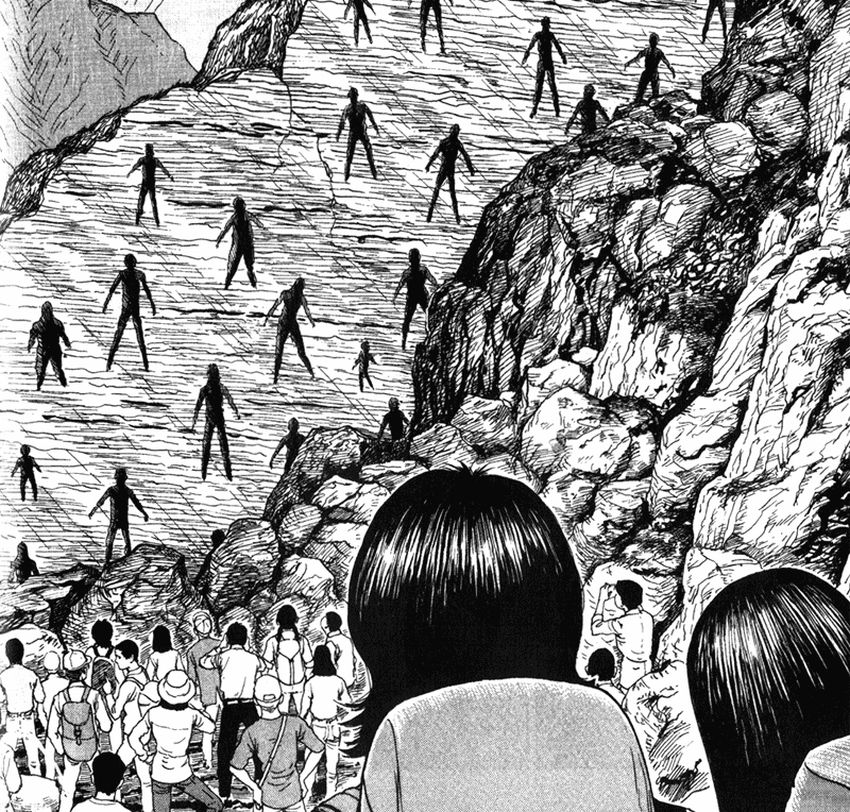

Sometimes his premises are strange, even ridiculous, but Junji Ito makes them work. The idea of a town haunted by spirals becomes one of the most disturbing and unique horror works of all time. Balloons that take on people’s faces and hunt them down become a nightmarish apocalypse. Even a story about human-shaped holes revealed after an earthquake becomes a setting for outlandish existential horror and deadly curiosity.

Junji Ito’s works stand out for their blend of masterful imagery and the narrative themes they explore. It’s worth noting that his nightmarish imagery and disturbing ideas often conceal deeper themes and ideas to ponder.

Cosmic Horror

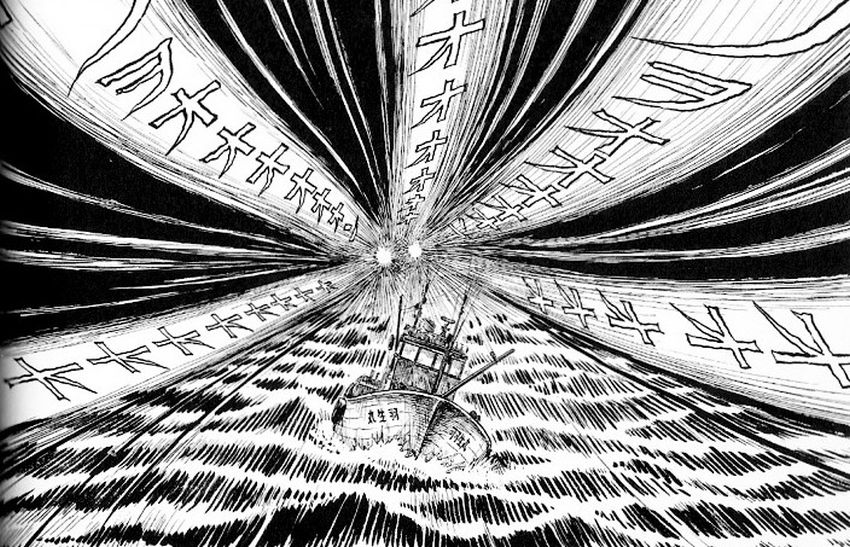

One can’t talk about Junji Ito without first discussing cosmic horror.

The genre was shaped by American horror writer H. P. Lovecraft. It centers on the idea that the most horrible realization is that humanity is ultimately meaningless in the greater scope of the universe. Worse, there are powers and beings far older and more powerful than we can imagine. They existed long before humans emerged and will remain long after we are gone. Our lives, our dreams, our problems are all meaningless in the vastness of the cosmos.

While Junji Ito is influenced by Lovecraft, he has created his own blend of cosmic horror, often stranger and more surreal than Lovecraft’s. Humans are powerless in Ito’s worlds; while some works, like Uzumaki, feature unknown forces or entities, much of his horror focuses on the intimate and mundane.

Another similarity is that cosmic horror and Ito’s work seldom feature central villains or antagonists. We don’t encounter evil in the traditional sense. Instead, the terror arises from our own realizations or from inexplicable forces at the edges of comprehension.

Junji Ito’s Visual Style

Junji Ito’s works are well known for his distinctive personal style. He brings his horrors to life through masterful ink and line work.

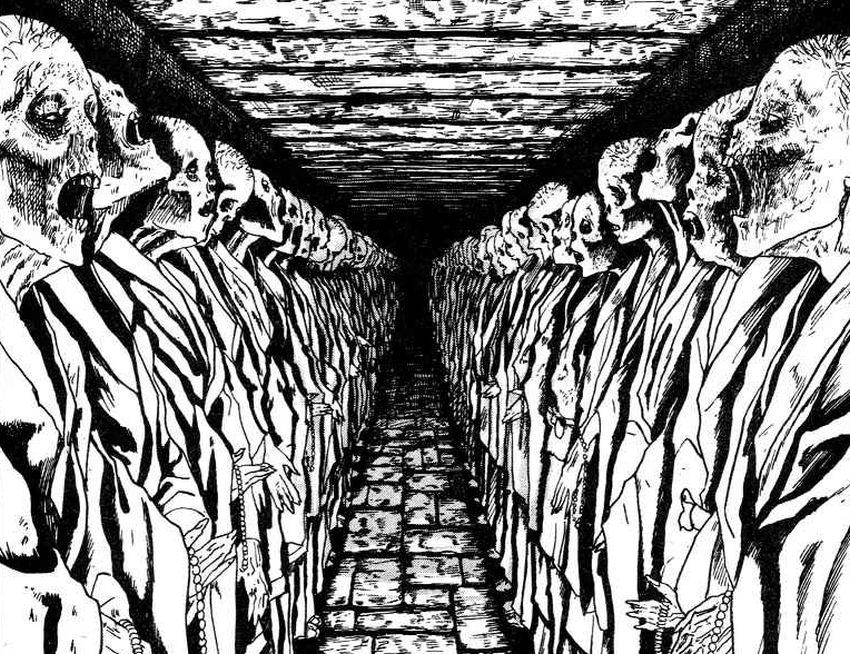

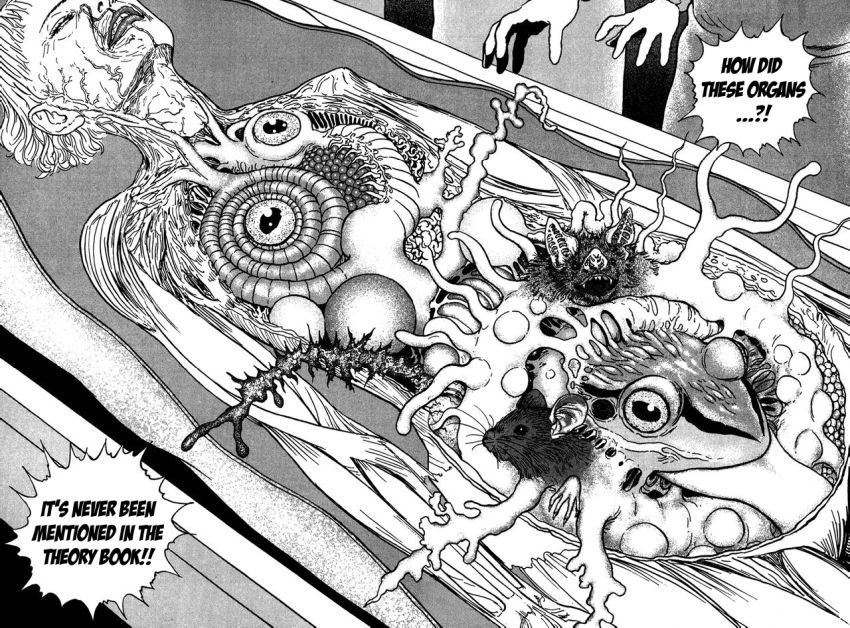

Ito uses detailed line work and bold, almost unsettling blacks to present grotesque, shocking imagery. While he uses shading, his pages mostly rely on lines to convey texture. Even gore and other unsettling elements, like blood, wet and squishy surfaces, are rendered almost entirely with lines. This gives them a unique look, adds detail, and lends a more visceral, nauseating quality.

He also leans on stark contrast, both in environments and in characters.

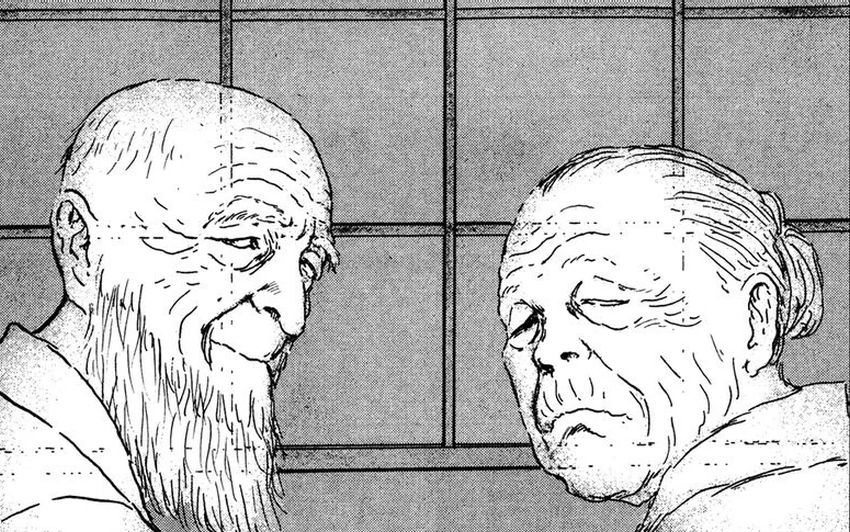

Ito’s style is most recognizable in his characters. They never blush and seldom show ordinary happiness. Instead, they are often emotionally muted, and when emotion appears it arrives as exaggeration.

His characters frequently look empty and lifeless even before the horror begins, especially in stories focused on personal horror or mental illness. You can see how badly they feel and how close they already are to the abyss that will swallow them. Their faces are marked by sunken cheeks, and their bodies are often sickly thin, almost skeletal. Dark circles around the eyes and unnatural irises signal heavy emotions such as depression and gloom.

He achieves this with minimal shading and heavy contrast across the face. Ito often focuses on the eyes and the mouth, using them to convey unnatural emotional reactions.

His characters often wear unsettling expressions. Whether smiles or sorrow, the features are grotesquely accentuated, giving them a surreal quality.

When the true horror arrives, Ito goes all out in depicting a person’s emotional response. Terrified expressions are so exaggerated they make us uncomfortable. Mouths gape, faces distort and elongate mid-scream, and eyes open wide.

Another signature element is his reliance on body horror and the distortion of the human form. He often avoids traditional monsters; instead, the terror comes from our own bodies. People are twisted, warped, and turned into shapes that barely resemble human beings. We see bodies curling into spirals, rotting into abominations, or stretching into elongated versions of themselves.

This reliance on body horror makes Ito’s work so terrifying. Often the horror does not come from outside, but from within our own bodies. It is both strangely fascinating and deeply disturbing.

Junji Ito’s Narrative Themes

As a writer, I’m often fascinated by Junji Ito’s work not only for its visual power but also for the recurring elements that shape his stories. While his work can be graphic, Ito employs a wide range of narrative themes to craft his unique blend of horror. His concepts are bizarre, sometimes even absurd, but incredibly creative. By contrast, his characters and settings are often as mundane as can be, at times even boring, which grounds the strangeness.

Many of his tales revolve around fears, obsessions, and phobias, showing what happens when people give in to them. Yet they also carry deeper meanings that may not be visible at first glance. Below, I discuss those elements in more detail.

Story-telling Conventions

Junji Ito’s work doesn’t follow traditional storytelling conventions.

Most of his characters are minimally characterized, and there is little overt character development. Instead, characters are often blank slates or exist to embody a specific fear or obsession.

The same applies to plot. Ito’s stories seldom rely on intricate plotting. More often he gives us a glimpse into someone’s life and lets us witness the horrible things that befall them. Above all, his work is about atmosphere, dread, and the gruesome demise of his characters.

Although Ito writes horror stories, there is seldom a clear, traditional antagonist. People are haunted by faceless entities, curses, higher powers, or their own psychological problems.

One of the biggest pitfalls in horror is the urge to explain what should remain inexplicable, or to add too many details. Ito seldom does this. Instead, he leaves us with the mystery, leaving us guessing and fearing the unknown. A prime example is Hanging Balloons. We never get an explanation of what the balloons are, where they came from, or why they exist. He simply shows what happens after they appear, lets us watch events through his characters’ eyes, and ends the story when their time on the page is over. The mystery remains intact and, with it, the horror.

Gyo is an example where Ito breaks this convention. Near the end, he offers a scientific explanation for the apocalyptic horror that unfolds, and it didn’t work for me. It feels almost comically absurd and undercuts the menace.

The Mundane and the Normal

Junji Ito’s stories often begin in normalcy. They don’t open with a dramatic backstory or by introducing an antagonist. Instead, they start in the most mundane places. We watch characters go to school, fall in love, or visit the hospital. It is in these ordinary settings that Ito slowly introduces the horror.

The same is true of the horror itself. In many stories, the threat emerges from mundane places or is triggered by everyday objects: records, laughter, hair, and even concepts such as spirals.

Many of his stories center on ordinary fears: the unknown depths of the ocean, claustrophobia, being watched, a sweaty, dirty mattress, or holes in a wall. Ito takes these anxieties up a notch. He twists them into something irrational and surreal, magnifies them, and turns them into phobias. At their core, though, they are fears many of us share.

Ito then bends these mundane settings and puts his ordinary characters under pressure until the world turns into horror. What begins as an everyday scenario becomes uncomfortable to watch; it is warped, and the surreal takes over.

This contrast between the mundane and the horrors he conjures is what makes his work feel so distinctive. We see it most in his characters. Their almost expressionless faces are twisted into masks of terror, with exaggerated features that barely resemble themselves. It is as if not only the story but also the characters are warped into something entirely different, something horrifying.

There are also stories grounded in reality. A great example is The Bully, one of his most realistic and most terrifying works.

Characters

It’s not only Junji Ito’s stories that are mundane; his characters are, too. They are nobodies, often blank slates who become entangled in Ito’s horrors.

They are frequently students or everyday people living ordinary lives. His characters are rarely the heroes of their stories; they are seldom smart or resourceful protagonists. Instead, they often serve as vessels through which Ito gives us a glimpse into his world of horrors.

Worse, they are sometimes foolish, driven by curiosity or desire. And when his characters do show strong emotion, it is almost always a single one. A fear, phobia, or desire becomes the defining trait, is often the only one they display, and it ultimately leads to their demise.

Junji Ito is a fantastic writer and artist, but he is not a character writer. His characters are merely there to be tested, and many feel like lambs led to the slaughter.

Irrational Fears

We all know irrational or childish fears. When we were young, we were afraid of the monsters under the bed, the doctor, strange neighbors, or even shadows.

As adults, we understand those are nothing more than irrational fears. There is no boogeyman, and there are no monsters out to get us.

Ito’s work, however, often features exactly these fears. That recognition gives his stories an uncanny feeling, because we have seen these scenarios before. We too were afraid to visit the doctor, and we too were afraid of the monsters under the bed, and even now we carry our own eccentricities and phobias. Ito explores and exploits them. He takes the most irrational, even silly fears, gives them life, and as a result his stories become much more terrifying.

Body Horror

Junji Ito is a master of body horror. He isn’t satisfied with people simply dying. Instead, he often distorts, warps, and twists them. This is visible not only in their ultimate demise, but also in how people change over the course of his stories. Characters who start out looking normal, even beautiful, become haunting, sick versions of themselves, or go insane as their sanity shatters.

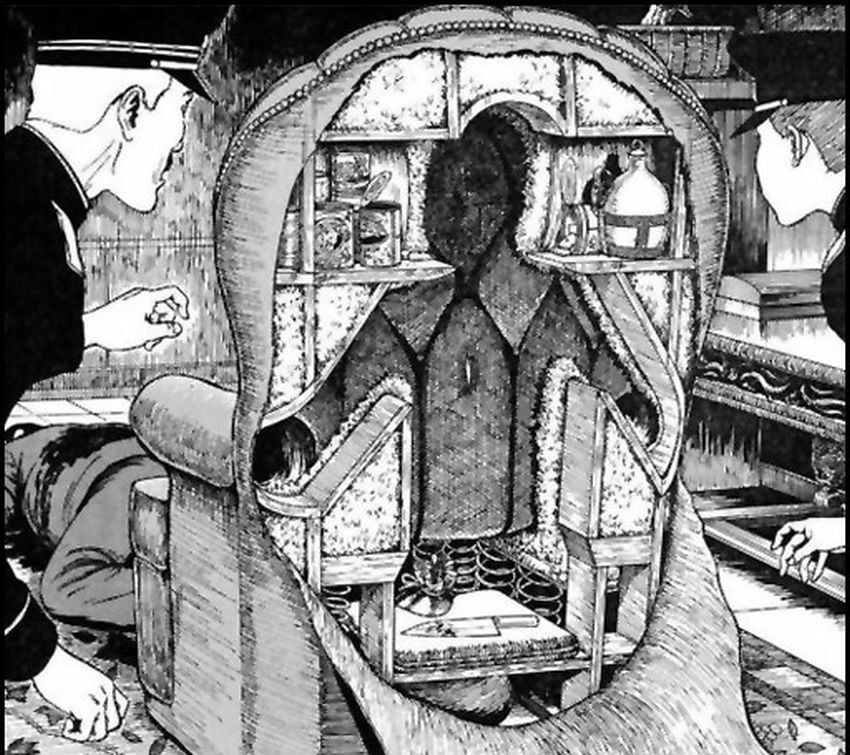

Two of the strongest examples are Dissection Girl and Uzumaki. The first features a disturbed woman who wishes to be dissected. Her wish is ultimately granted at the end of the story, culminating in one of Junji Ito’s most fantastically disturbing panels. It is revealed that not only her mind but also her body is heavily distorted. Uzumaki, on the other hand, is a three-volume masterpiece about a small town haunted by spirals. Over the course of the story, many inhabitants become obsessed with spirals and are warped and twisted until their bodies reflect the spiral in various horrible ways.

Junji Ito’s brand of body horror is always a disturbing delight to look at, and it often renders his characters almost unrecognizable.

Mental Horror

One of Junji Ito’s most common tropes is mental illness. Depression, fears, phobias, and obsessions are often the focus of his stories.

Yet Ito isn’t satisfied with merely exploring them. Often, an irrational fear or phobia is only the starting point, and over the course of the story he amplifies and distorts it until it ends in utter madness.

His characters’ minds get distorted and change much like their bodies. As eyes bulge and mouths hang open in terrible screams, their minds, too, are inevitably broken.

Powerful emotions and erratic, irrational behavior are common in his work and almost commonplace among his characters. They are eccentric weirdos, people whose entire being revolves around a single trait, often a personal blend of mental illness, fear, or phobia.

Obsession is the leitmotif in Junji Ito’s Tomie, which features a woman so beautiful that any man who sees her becomes obsessed. Many other stories also center on obsession. It can be caused by love, animosity, jealousy, or even the urge to possess a particular object. Each of these stories ends with people giving in to their obsession, being changed by it, and ultimately facing dire consequences.

Love, too, is something Ito often exploits and distorts. What begins as a harmless crush soon becomes a dangerous obsession that drives people mad. Strong examples include Tomie, Lovesick Dead, and the chapter Jack-in-the-Box in Uzumaki.

Insanity, Despair and the Inevitable End

As mentioned before, Junji Ito often pushes his characters’ fears and phobias to their limits, driving them into despair and insanity.

The reason is simple: his characters are often inevitably doomed. Similar to figures in the works of Franz Kafka or H. P. Lovecraft, they have little power over their world.

We see it clearly in Uzumaki, where an entire town becomes an inescapable hell and characters realize there is no hope, no way out. In a similar way, The Enigma of Amigara Fault toys with curiosity and with inevitable fate. People flock to the human-shaped holes that mirror them and, compelled by a primal urge, enter despite themselves.

Existential dread sits at the core of our being. As humans, we are the only creatures on this planet who know that we will die one day, and there is nothing we can do about it.

Ito’s stories are full of this dread, and his worlds are harsher than our own, stranger, more dangerous, and indifferent to the people within them. The horror often arises from the most mundane places, showing that nothing is safe in Junji Ito’s world. There are no safe spaces, and even the most ordinary thing can lead to a terrible, irreversible event.

Deeper Meaning and Themes

Town Without Streets is a prime example. It examines privacy and pushes it to its extremes. What would you do if privacy no longer existed? Would you reject such a world and fight against it, or accept it and discard the idea of privacy altogether? It is a topic that feels even more relevant today.

Another strong example is Long Dream. It asks whether endless dreaming could be a way to defeat death. Is it better to be trapped in a dream forever than to die? Is even a never-ending nightmare preferable to ceasing to exist?

Isolation is another dominant theme in Ito’s work. As mentioned before, many of his characters struggle with problems and isolate themselves from society.

Ito presents a different view of isolation in Army of One. Safety in numbers is usually the rule in horror. In Army of One, however, he twists that idea, and those who stay alone, who truly isolate themselves, are the ones who remain safe. It is a strange story, but one ripe with meaning. It seems to point to our urbanized society and the forced social interactions common in it, especially in Japan. Is it ultimately better to remain on your own than to join an often forced social life?

Lingering Farewell is a study of holding on and refusing to accept the death of loved ones, and it is also one of Junji Ito’s best stories.

Black Paradox is one of Ito’s weirdest works, but in its later parts it raises an interesting question. In the story’s context, humanity uses its own souls as a new source of energy. The broader idea is clear: we may bring about our own end through greed and the hunger for power.

Hanging Balloons may seem nonsensical at first glance, but there is more here than meets the eye. The first person to die is Terumi, an idol. If you are familiar with Japanese pop culture and the idol industry, you know suicides are an unfortunate reality. Yet the story is not simply a critique of the idol system.

Similar to The Enigma of Amigara Fault, the story engages with Sigmund Freud’s death drive, our fascination with self-destruction and the compulsion to move toward it. Most of us suppress those thoughts, but some do not.

While The Enigma of Amigara Fault shows characters driven by a strange, almost supernatural obsession to find their holes, Hanging Balloons takes a different route. The balloons are a personification of the death drive, and the story functions as an allegory of that impulse catching up with and preying upon people.

Examples like these show that while Junji Ito is predominantly an artist who creates visual nightmares, his work often carries deeper meaning.

It always strikes me that works as bloody, surreal, and twisted as Ito’s can also convey layered themes. That added depth gives readers something to ponder when they want more than blood and gore alone.