Depressing manga can be powerful, not because they aim to shock or devastate, but because they linger. They’re stories of emotional erosion and psychological collapse that stay with you long after you finish reading. They leave behind unresolved feelings, uncomfortable truths, and characters who don’t fully heal.

This list focuses on manga that confront depression head-on, whether personal, societal, or existential. Some explore it through trauma, guilt, and abuse. Others explore isolation, alienation, or the slow realization that life has become unrecognizable. These aren’t stories of momentary sadness. They’re defined by emotional weight accumulated over time, and the lasting damage it leaves behind.

These manga aren’t all the same, and this list aims to reflect that range. Some series are overtly bleak, filled with violence, cruelty, or relentless suffering. Others are quieter and introspective, centered on memory, regret, or the inability to move forward. What unites them isn’t just depression. It’s how it reshapes identity, relationships, and perception itself.

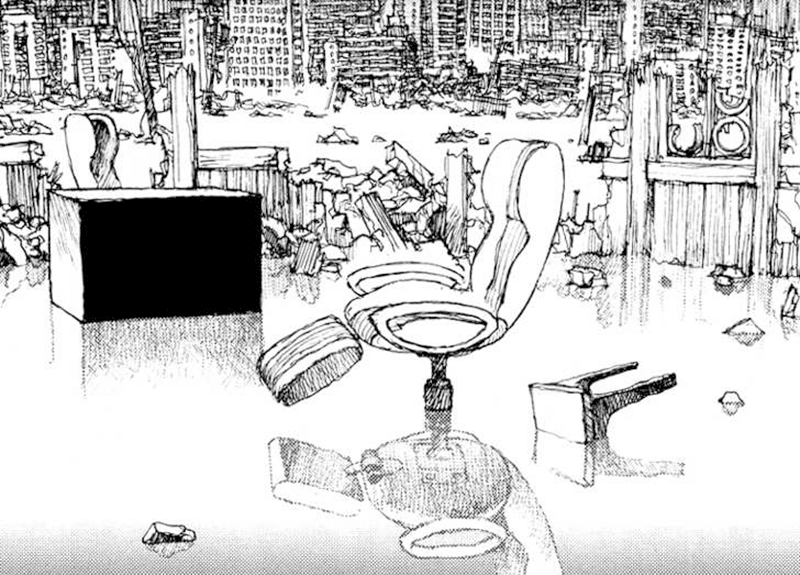

Several entries lean toward psychological horror. Blood on the Tracks depicts the slow warping of ordinary life and family bonds. Others, such as Yamikin Ushijima-kun and Nijigahara Holograph, expose the depth of human depravity, and show how easily ordinary people slide into despair. Works like Utsubora and Helter Skelter take a more intimate approach, focusing on characters in the art and entertainment industries, and how ambition and obsession gradually destroy them. You’ll also find character-driven narratives like Bokutachi ga Yarimashita and Boys on the Run, about ordinary people trapped in hells of their own making.

All of these depressing manga depict despair in different forms, but all land at the same devastating conclusions. Whether through intimate family drama, personal failure, or social decay, they show what happens when people stop believing change is possible.

Mild spoiler warning: I avoid major plot revelations, but I do reference themes and key moments to explain why each series belongs here.

With that said, here’s my list of the best depressing manga that linger (last updated: January 2026).

17. Boys on the Run

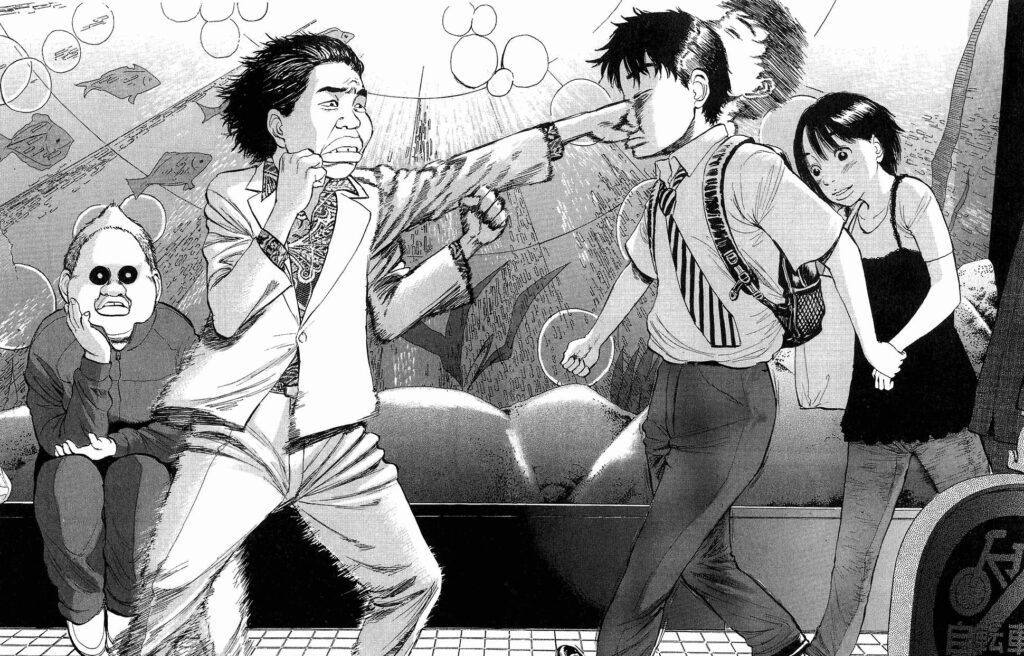

Boys on the Run earns its place on a depressing manga list because of its protagonist, not shock value or extreme tragedy. Watching 26-year-old Tanishi repeatedly sabotage his own life is exhausting, frustrating, and quietly devastating in a way that feels uncomfortably real. This is not a story about hitting rock bottom once. It’s about never climbing out in the first place.

At its core, Boys on the Run is a character study of what it means to stay stuck. Tanishi works a dead-end job, lives with his parents, and drifts through life with no real direction or confidence. Opportunities appear in front of him with surprising regularity, whether through romance, work, or boxing. Each time, he finds a way to ruin it. Not out of cruelty or malice, but out of insecurity, indecision, and an almost impressive inability to grow. The result is a portrait of a man trapped inside his own limitations.

What makes this manga so depressing is how recognizable it feels. Tanishi isn’t an outlier or an extreme case. He’s painfully normal. He lacks talent, charisma, and discipline, but he also lacks the insight to change. Watching him fail is infuriating, yet that frustration comes from proximity. Many readers will recognize a piece of themselves or others they know in his excuses, his self-pity, and his fleeting bursts of motivation that never last.

Rather than portraying depression as overt despair, Boys on the Run presents it as lethargy. Tanishi doesn’t collapse in a dramatic fashion. He simply stays where he is. His failures pile up quietly, turning embarrassment into shame and shame into resignation. Over time, it becomes clear that the most depressing aspect of life isn’t what happens to him, but that he never changes.

Kengo Hanazawa’s expressive and rough art style reinforces the tone. Faces contort with humiliation, panic, and brief flashes of hope that vanish moments later. Nothing feels glamorized. Boxing scenes, romantic moments, and workplace interactions all carry a raw awkwardness that mirrors Tanishi’s inner state. The manga often feels ugly, both visually and emotionally, but it feels honest.

This is a depressing manga at its most grounded. There are no grand metaphors or philosophical monologues, just a man failing in small, cumulative ways. Boys on the Run offers endurance more than catharsis or redemption. It asks the reader to sit in frustration, secondhand embarrassment, and the uncomfortable realization that some people never transform. They just keep going, unchanged.

For readers drawn to stories about quiet despair, personal stagnation, and the psychological toll of being ordinary, Boys on the Run is a painfully effective experience. It doesn’t aim for sadness. It just wears you down.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

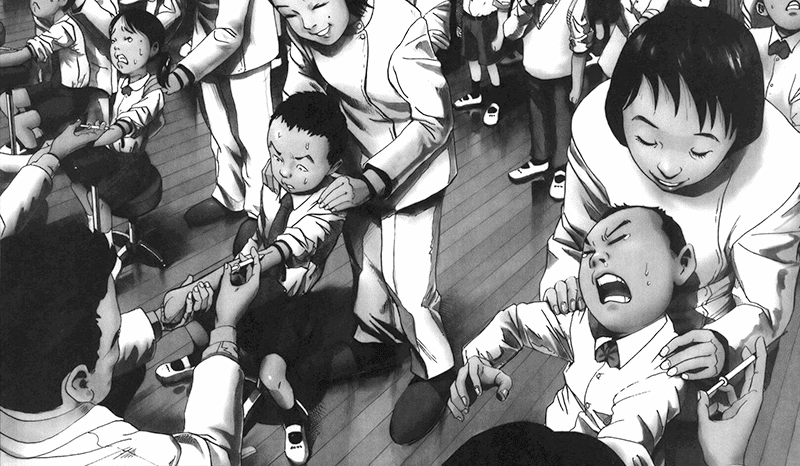

16. Bokurano

Bokurano sits in the same grim tradition as Evangelion, turning the idea of children piloting mechas into a horror premise rather than a power fantasy. The central hook is simple and cruel: a group of middle schoolers stumble into a game that asks them to pilot a massive robot to protect the world. Then the cost reveals itself, and what looks like an adventure becomes a nightmare.

What makes Bokurano a depressing manga isn’t just the inevitability baked into its premise, but the way it frames everything around it. Each fight is less about spectacle than consequences. People die, cities get leveled, and the kids are forced to reckon with the fact that heroism doesn’t erase the damage. The series keeps returning to the same quiet question in different forms: what do you do with your remaining time when the world expects you to die for it?

Bokurano works like a chain of character studies, shifting focus from child to child, each with their own emotional backstory. Some of the kids grasp for meaning, some detach, some spiral, and some lash out. The darkness isn’t confined to the cockpit either. Several children carry their own trauma into the story, and the manga doesn’t flinch from topics such as abuse, exploitation, and toxic families. That grounding makes the premise hit harder, because the suffering doesn’t feel like a science-fiction tragedy. It feels like human misery, using science-fiction as the lens.

I first encountered Bokurano through its anime adaptation, but it’s the manga version that fully commits to the bleakness. It leans hard into the uglier implications, and it’s more willing to sit in discomfort instead of only hinting at things. That said, it’s also a divisive work. The deadpan tone, the occasional clunky philosophical interlude, and characters who don’t react like real kids can be jarring. For others, the emotional numbness reads as the point, another symptom of a situation too large to process.

Either way, Bokurano leaves a mark. It’s less interested in saving the world than in documenting the cost, and how little comfort anyone gets in return. If you want a depressing manga that’s fatalistic, ethically nasty, and focused on psychological erosion rather than catharsis, this one is hard to forget.

Genres: Drama, Psychological, Science-Fiction

Status: Completed (Seinen)

15. Ikigami

Ikigami is depressing in a brutally clinical way. It doesn’t begin with a tragedy that spirals out of control. It begins with paperwork. In this world, the National Welfare Act selects a small number of young citizens to die for the stability of the country, and they are told exactly twenty-four hours before their death. The one-day countdown is brutal, but the deeper despair is what it implies: society has normalized state murder.

The manga centers on Kengo Fujimoto, a government messenger tasked with delivering the death notice called Ikigami. His job forces him face-to-face with people at their rawest. Each vignette follows a recipient’s final day, and the emotional range is what makes it hit so hard. Some characters try to repair past relationships, some rage against the system, and others simply collapse under the weight of knowing there’s no way out. Even the best outcomes carry a cold aftertaste.

What separates Ikigami from stories that use death as shock value is its focus on resignation. It’s not just about the fear of dying. It’s about how quickly people accept the unacceptable, and how isolation intensifies once the public knows they’ve received an Ikigami. Friends, employers, and even family members often react in ways that reveal selfishness, cowardice, or desperation. The most depressing moments aren’t always the ones where someone breaks down. They’re the moments where everyone behaves as if this is normal.

Fujimoto’s perspective adds another layer of numbness. He’s not a hero, and he isn’t framed as one. He’s a cog in an unfeeling machine, and the manga uses this to underline how systemic cruelty survives. Not through overt villains, but through ordinary people doing their jobs, repeating the same phrase, and pushing responsibility upward until no one feels accountable.

Motoro Mase’s grounded art style suits this tone. There’s no hint of melodrama. Faces carry subtle panic, denial, and shame, but this restraint makes the despair more believable. It’s bleak without being performative, and it lingers because it feels plausible as a thought experiment about societal control.

If you’re looking for a depressing manga that treats depression as societal, not personal, Ikigami is one of the sharpest examples. It isn’t asking whether life is fragile. It’s showing what happens when a country turns fragility into policy, and indifference becomes the norm.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Dystopian

Status: Completed (Seinen)

14. Berserk

Most people come to Berserk for the brutality, the creature design, or Kentaro Miura’s unmatched art. What hits harder is how relentless the series treats trauma as something you carry, not something you conquer. Beneath the battles and spectacle sits a story about emotional damage that shapes identity, intimacy, and perception.

The setting is bleak in a way that feels realistic rather than theatrical. War isn’t romanticized. Cruelty isn’t rare. Bands of mercenaries leave ruin behind, institutions that claim moral authority commit atrocities, and monstrous forces prey on people. The atmosphere matters because it never lets the characters feel safe. Recovery requires stability, and Berserk refuses to offer it.

Guts is the clearest example. His childhood is defined by violence and abuse, and the series doesn’t frame those experiences as mere backstory. They remain open wounds. You see it in how he reacts to closeness, how he panics during gentle moments, and in how quickly tenderness becomes unbearable. The early version of Guts, cold and abrasive, is less about edginess and more about survival. He’s built walls to protect himself from a world that’s only made him suffer.

The story’s central relationship with Griffith deepens that depression further. It’s not only a clash of ideals and ambitions. It’s a lesson in how trust can be used, and how betrayal can rewrite someone’s entire internal world. The aftermath of the Eclipse doesn’t just fuel revenge. It poisons everything around it, including the part of Guts that still longs for connection.

Casca’s arc is the cruelest extension of that theme. She’s introduced as capable and battle-hardened before her mind is fractured by an act of unfathomable violence. For a huge portion of the narrative, she exists as a living reminder that trauma can erase self.

That’s why Berserk belongs on a depressing manga list. Its sadness isn’t a single tragic event. It’s the long, grinding toll of survival in a world that keeps wounding you, and keeps finding new ways to reopen those wounds.

Genres: Horror, Dark Fantasy, Action, Tragedy, Psychological

Status: (continued by Kouji Mori after Kentaro Miura’s death)

13. Aku no Hana

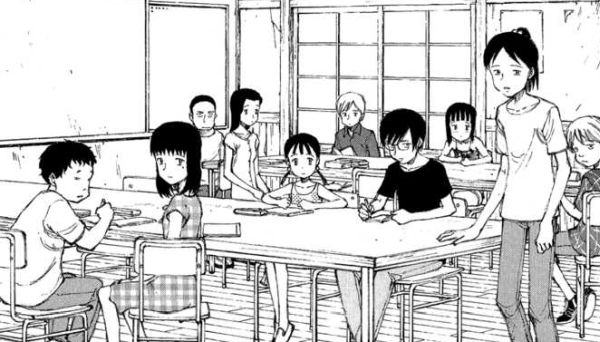

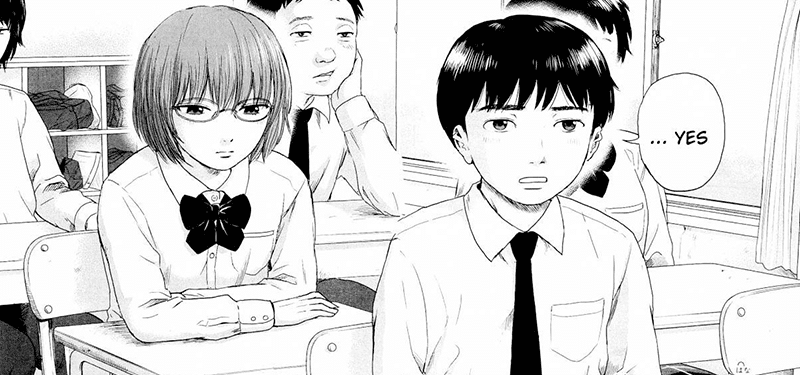

Few manga capture the misery of adolescence like Aku no Hana. It isn’t tragic or sweeping. It’s suffocating, humiliating, and intimate, built out of the kind of mistake that feels small at first and life-defining a week later. For a story set in an ordinary middle school, it has some of the most emotionally punishing atmosphere in manga.

Takao Kasuga is introduced as a boy who wants to be seen as refined and sensitive, but is terrified of being exposed as strange or pathetic. That insecurity becomes the starting point of the series. A single impulsive theft, motivated less by lust and more by self-loathing and curiosity, gives Sawa Nakamura the leverage she needs. Her blackmail works because it hits something deeper than the fear of getting caught. It targets his desperate need to uphold the image he created of himself.

What makes Aku no Hana land as a depressing manga is how it treats rebellion as another form of captivity. Nakamura frames transgression as freedom, but her demands create a system where shame is both punishment and proof of belonging. Saeki, meanwhile, represents the fantasy of normalcy, and the more Kasuga tries to win her approval, the more he realizes he can’t go back to who he was. Nobody here feels stable. Everyone hides behind a facade, and the cracks are showing.

Shūzō Oshimi’s character work helps the manga stand out. Kasuga isn’t a sympathetic victim, and Nakamura isn’t a glamorous agent of chaos. They are emotionally raw kids, using whatever they can to create meaning out of boredom, grief, and resentment. The escalation in the first half might spiral into unrealistic territory, but it also shows how teenage emotions can make ordinary spaces feel like prisons.

The art style strengthens the claustrophobia. Faces are vulnerable and unflattering. Silences hang heavy. Small-town streets and classrooms feel exposed, as if there’s nowhere to hide from the prying eyes of others.

The latter half slows down and pivots into consequences, reflection, and rebuilding. It won’t satisfy readers who are looking for escalation, but it complements the first half in a way that feels earned, and even hopeful. Still, it’s the earlier stretches that linger, the part that turns self-discovery into something raw and painful.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Coming-of-Age

Status: Completed (Shonen)

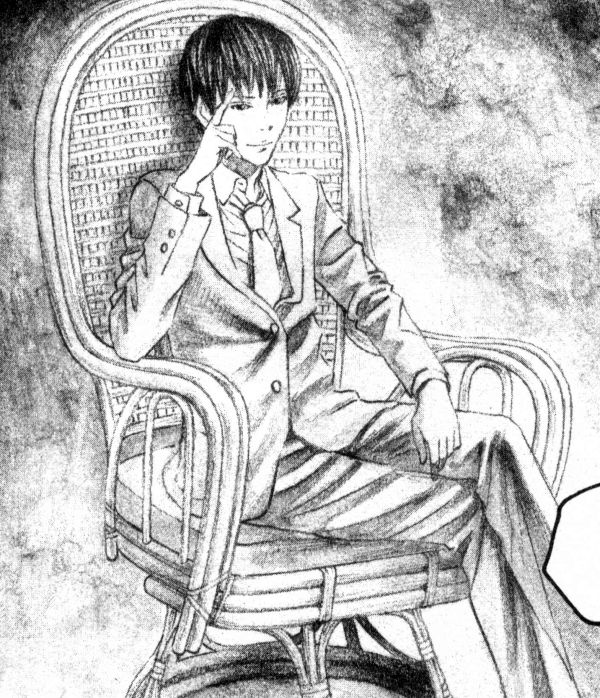

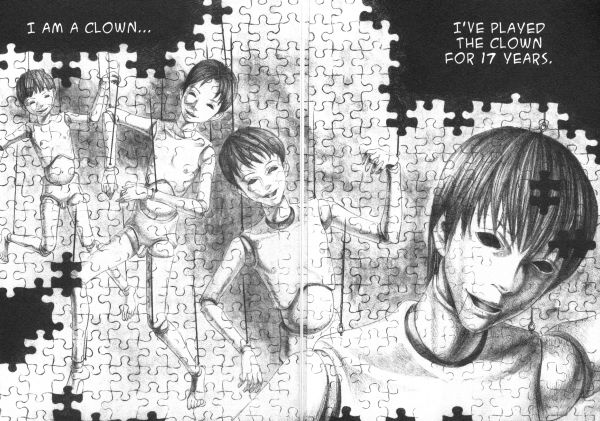

12. No Longer Human

Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human has its reputation for a reason. It’s one of Japan’s defining portraits of shame, alienation, and self-erasure, and Usamaru Furuya’s modern manga adaptation doesn’t soften any of that. Framed as an online diary discovered by Furuya himself, the story reads like a document that was never supposed to be found, but still pulls you in deeper.

At the center is Youzou Ooba, a young man who experiences other people as a threat. His solution isn’t violence or rebellion. It’s performance. At first, he tries to get people to laugh and does whatever he can to keep his underlying panic at bay. Then he tries to overcome emptiness through sex, substances, and self-sabotage. The most depressing part isn’t any single moment. It’s the way Youzou’s life narrows until even ordinary days feel like a slow collapse.

Furuya’s strongest choice is how he treats Youzou’s destructiveness as not only personal, but also environmental. Bad influences matter, and so do social expectations, money, and the cruelty of other people who sense weakness and exploit it. Youzou isn’t romanticized as a doomed artist or a misunderstood genius. He’s someone who can’t hold on to stability, and who confuses intimacy with self-harm because that’s the only form of contact that doesn’t require real trust.

Visually, the adaptation stays grounded, but it knows when realism isn’t enough. At key moments, the art turns into metaphor, rendering Youzou as a puppet, or other people as invasive presences rather than individuals. These sequences reveal his inner state without ever spelling it out, making the manga’s bleakness feel real rather than theatrical.

If you’re looking for a depressing manga that focuses on sustained emotional erosion, No Longer Human stands out. It’s not a mere tragedy, and it isn’t interested in recovery. It’s a study of a mind trying to retreat from life, even when it’s begging to be saved. Other adaptations exist, including Junji Ito’s, but Furuya’s version feels closest to the novel’s depiction of depression as a long, humiliating unraveling.

Genres: Psychological, Drama

Status: Completed (Seinen)

11. Fire Punch

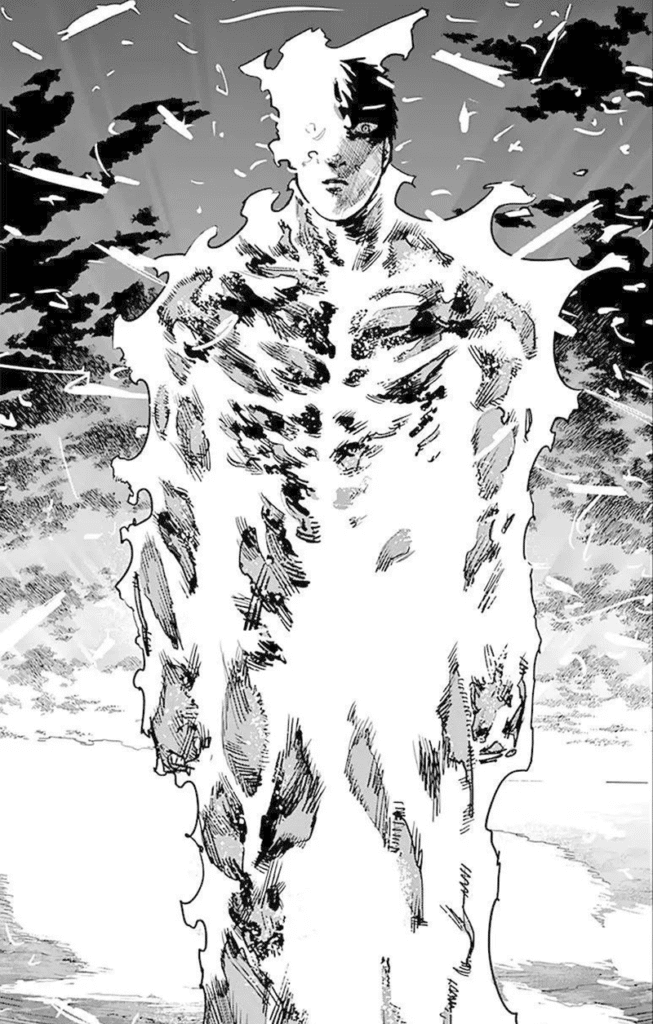

Fire Punch earns its place on a depressing manga list through attrition more than through tragedy. Tatsuki Fujimoto builds a world where suffering is the norm. It starts with a brutal premise, then grinds it down until revenge, identity, and even hope evaporate.

Agni’s situation is the clearest example. Gifted with regeneration, he becomes the victim of punishment that never ends. His body won’t die. He’s trapped in constant, agonizing pain, but forced to keep going because stopping changes nothing. His drive isn’t heroism; it isn’t even dignity. It’s his way of clinging to the one person he loved. That makes Agni’s struggles less inspiring than unsettling.

Fujimoto’s setting amplifies that despair. Communities don’t just fail; they rot into systems that normalize atrocities. Cannibalism, exploitation, and public cruelty aren’t treated as exceptions. They’re treated as just another part of life. Fire Punch is bleak in a way that feels institutionalized, as if the world itself is designed to break people until morality vanishes.

Midway through, the manga turns into something even stranger. Togata arrives as a walking contradiction: funny, charismatic, deeply damaged, and obsessed with turning Agni’s suffering into a movie. That shift matters because it reframes the violence as spectacle. It’s as if the series is asking what it means to watch misery, turn it into a narrative, and keep demanding escalation. That said, Togata is also one of the most human characters in the story, not because they offer comfort, but because they represent another kind of trapped existence, rooted in a body and identity that can never be changed.

By the time the story pushes into its later arcs, the revenge structure has become hollow. Fire Punch becomes a study in what’s left when purpose collapses, and when survival stops feeling meaningful. That’s why it belongs among depressing manga, even if it’s chaotic and often absurd. The series doesn’t aim for catharsis. It goes for the numb aftermath, the kind that makes you sit and wonder what you just read.

Genres: Horror, Gore, Post-Apocalyptic

Status: Completed (Shonen)

10. Blood on the Tracks

Shūzō Oshimi has a talent for revealing the violence hiding inside ordinary life. Blood on the Tracks is his most intimate take on that idea, a story that treats the family home as a closed system where love, dependence, and fear become impossible to separate. It reads like psychological horror, but what makes it linger is how relentlessly depressing it is.

The setup is deceptively simple. Seiichi Osabe is a quiet middle-schooler living under the shadow of his mother, Seiko, whose affection is constant and smothering. At first, her control isn’t drenched in cruelty. It’s overprotective, possessive and hard to name. Then an early, shocking moment traps Seiichi in a relationship he can’t escape, and can’t explain to anyone. From there, it becomes a study of emotional captivity, where the worst punishment isn’t violence but the way a child’s sense of reality gets rewritten.

Oshimi weaponizes pacing. He stretches moments until they feel unbearable, letting silence do the work that dialogue usually covers. A single expression can dominate an entire chapter, and the effect is crushing. You don’t just understand Seiichi’s paralysis; you feel trapped in it. The art reinforces that claustrophobia through tight framing, lingering close-ups, and backgrounds that fade into irrelevance because the real threat is the person closest to you.

As a depressing manga, Blood on the Tracks hits harder because it corrupts something basic. A parent is supposed to be the one place you can retreat to without thinking. Oshimi turns that bond into a trap. Seiichi isn’t just frightened; he’s reshaped, trained to second-guess his instincts, and to apologize for his own fear.

The bleakness deepens when Seiko becomes more than a villain. Later revelations reframe her as someone profoundly damaged, the kind of person who needed help long before she had a child to cling to. That doesn’t soften or excuse what she does, but it makes the story even heavier. You’re not watching an evil presence invading a family, but one built around damage.

If you’re looking for psychological realism over plot mechanics, this is one of the most devastating examples of a depressing manga. It’s quiet, controlled, and emotionally brutal in ways that feel uncomfortably plausible.

Genres: Horror, Psychological, Tragedy, Philosophical, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

9. Utsubora: The Story of a Novelist

Utsubora: The Story of a Novelist hitsharder than most stories about artists because it isn’t interested in romanticizing the creative life. It treats writing as something that magnifies insecurity, envy, and longing until a person confuses craft with identity. That’s why it belongs on this depressing manga list. The sadness here isn’t a single tragedy. It’s the slow discovery that life can be built around an illusion, and that the fall from it can be quiet, elegant, and final.

Shun Mizorogi is introduced as a novelist who’s already past his peak. The attention that once validated him is fading, and his relationship to his own work is deteriorating. When a young woman named Aki Fujino reaches out to him and then dies by suicide, the series doesn’t play it as melodrama. It’s presented as an intrusion that exposes how fragile Mizorogi’s sense of control is. Soon after, Aki’s identical twin Sakura Miki enters the story, and the manga turns into a psychological study of authorship, imitation, and identity. A plagiarism scandal surrounding Mizorogi’s latest work becomes the external crisis, but the real collapse is internal. He keeps choosing self-preservation over honesty, and then watches those choices destroy him.

What makes Utsubora so bleak is how thoroughly everyone feels damaged in their own way. Mizorogi’s desperation isn’t about poverty or survival. It’s desperation for relevance, the fear of becoming ordinary, and the shame that comes with needing praise to believe you exist. Aki’s absence haunts the narrative, reminding us of what happens when a person’s pain is ignored until it’s irreversible. Sakura’s presence adds a colder, more unsettling dimension, as if grief has become strategic. The story never needs to spell these themes out, but shows them via the character’s actions.

The art of Asumiko Nakamura is a huge part of this effect. The linework is delicate and restrained, and faces are drawn with a calm that feels almost eerie in dramatic scenes. That composure creates a lingering unease, as if people are merely watching as their lives derail. Even the eroticism carries a muted melancholy, as if it’s less about pleasure and more about connection.

Utsubora rewards careful reading, but it’s not a mystery for the sake of it. It’s a portrait of creative decay and identity erosion. It leaves you with the uncomfortable sense that the most catastrophic endings don’t arrive with noise or theatrics, but just happen quietly. It’s a devastating, depressing manga because it’s intimate, psychologically sharp, and artistically restrained.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Mystery

Status: Completed (Josei)

8. Shigurui

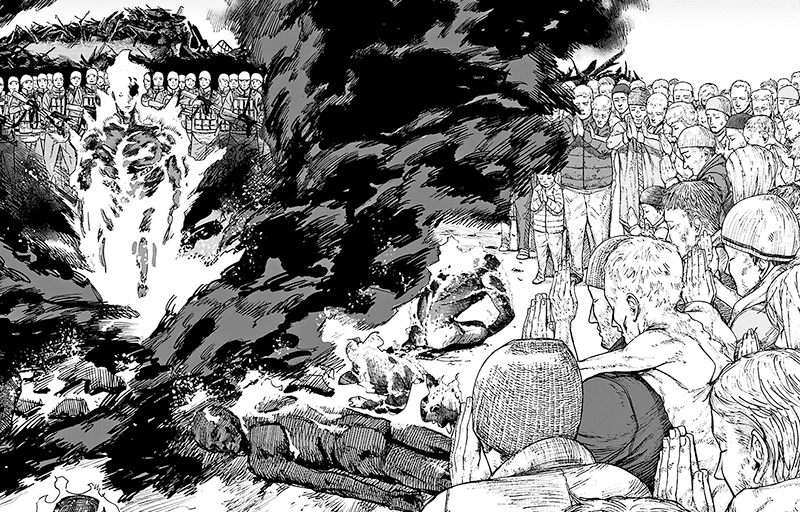

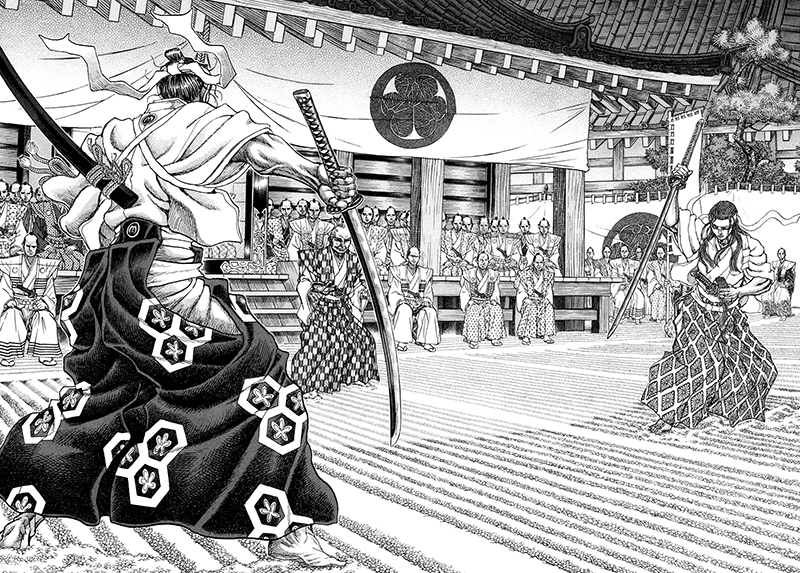

A samurai manga can look like an odd pick for this list, but Shigurui earns its place through tone. It isn’t just violent. It’s emotionally devastating, built around a society where obedience is treated as a virtue, cruelty is routine, and human life is weighed against pride, status, and inheritance. The result is one of the coldest portrayals of power I’ve seen in manga, and one of the most punishing experiences on this depressing manga list.

The story opens with a spectacle that immediately exposes the era’s moral decay. The daimyo Tadanaga Tokugawa stages a tournament where men fight with real blades, and the first bout is between a one-armed swordsman and a blind, lame opponent. Shigurui works backwards to explain how those two men ended up in that position, and the answer isn’t romantic tragedy. It’s institutional conditioning. Dojo hierarchy, patronage, and political pressure turn people’s rivalries into something inescapable, and the manga treats it as a machine that grinds people down until they’re useful or ruined.

What makes the series so bleak is how it frames skill and discipline. A samurai’s dedication can be impressive, but Shigurui never lets admiration become comfort. Training becomes obsession, self-harm, and submission to a code that has no mercy for the weak. Gennosuke Fujiki and Seigen Irako read less like heroes and more like case studies in how a culture can distort ambition into self-destruction. Their rivalry isn’t a clash of ideals. It’s the predictable outcome of a system designed to manufacture violence and call it honor.

The treatment of women is just as bleak. Lady Iku and Mie aren’t allowed lives of their own the way men are. They’re property, leverage, or proof of legitimacy, which makes the setting’s brutality feel broader than swordplay. The point is clear: no one here is free, and bodies are controlled, traded, and punished.

Visually, the manga sharpens the despair. Takayuki Yamaguchi draws with obsessive clarity, making serene landscapes and architecture feel eerily calm beside sudden, surgical gore. The violence lands hard because it isn’t stylized as heroic. It’s matter-of-fact, anatomical, and brutal. Beauty and horror share the same page, but neither offers any relief.

Shigurui has structural flaws. Later sections drift into unresolved side plots, and the ending can feel abrupt, likely because the adaptation never covers the full scope of the source novel. Still, the conclusion it delivers fits the story’s main themes. There’s no catharsis, no redemption, and no real sense that anything could’ve turned out differently. If you want a depressing manga that treats despair as societal rather than personal bad luck, Shigurui is relentless.

Genres: Action, Historical, Drama, Tragedy, Martial Arts

Status: Completed (Seinen)

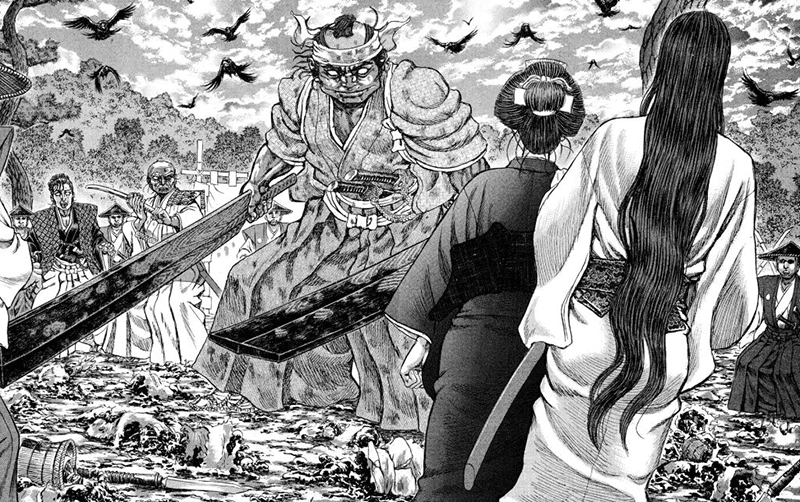

7. Yamikin Ushijima-kun

Calling Yamikin Ushijima-kun bleak undersells what it’s doing. Manabe Shōhei builds the series around the moment people realize they’ve run out of options. The illegal loans are only the entry point. What follows is desperation, self-deception, and quiet collapse, where the real horror is how ordinary each downfall plays out. If you want a depressing manga that treats misery as routine rather than spectacle, this one is hard to top.

Ushijima’s business model is surprisingly simple in the most predatory way possible: crushing interest, short deadlines, and zero excuses. The people who take the deal aren’t thrill seekers. They’re addicts, fragile families, small-time dreamers, and exhausted workers who mistake a temporary fix for a way out. That mix matters, because the series isn’t just focusing on the foolish. It’s showing how easily shame, hubris, or bad luck can push someone into a system that’s designed to keep them there.

Each arc plays out like a case study in social failure. Debt isn’t treated as a number on a page, but as a force that reshapes identity. Characters lie to partners, abandon friends, double down on gambling, or accept humiliations they never would otherwise. Even when they choose their next steps, the choice is usually just another kind of damage. The manga keeps returning to the same brutal reality: repayment rarely means money alone. It means leverage, bodies, and dignity.

What makes the series especially grim is the wider ecosystem around Ushijima. He’s exploitative, and often cruel, but the story repeatedly introduces people who are worse, including scammers, violent criminals, and corporate predators who hide behind respectability. That escalation creates a bleak outlook. You might end up rooting for Ushijima, not because he’s redeemable, but because the surrounding world makes him almost sympathetic. It’s one of the manga’s sharpest points about morality in an environment that’s entirely rotten.

Manabe’s art reinforces that tone. People look tired, sweaty, and painfully real, and this ugliness never feels stylized. Scenes play out with an oppressive inevitability, as if society itself decides what happens to the people who fall behind.

The main criticism is also part of its identity: Yamikin Ushijima-kun can feel relentless. The series offers the occasional flicker of hope, but it’s comfortable pushing characters past the point where lessons are learned. That intensity is exactly why it belongs here. It’s a depressing manga that refuses to pretend consequences are neat, recoverable, and fair.

Genres: Crime, Psychological, Drama

Status: Completed (Seinen)

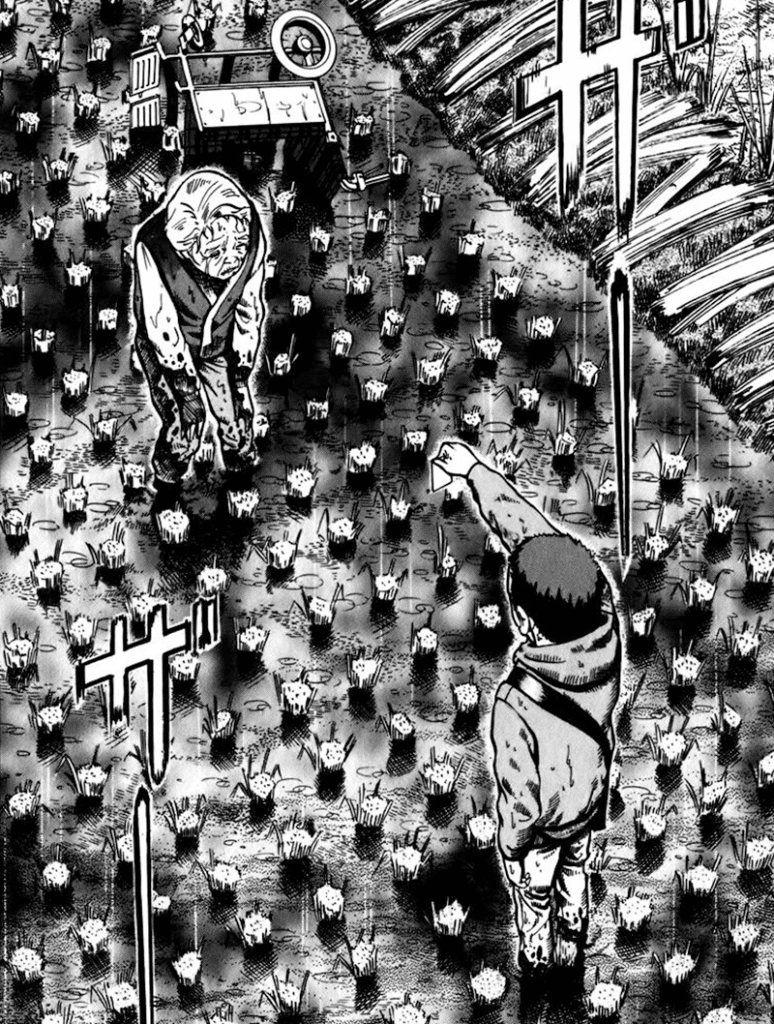

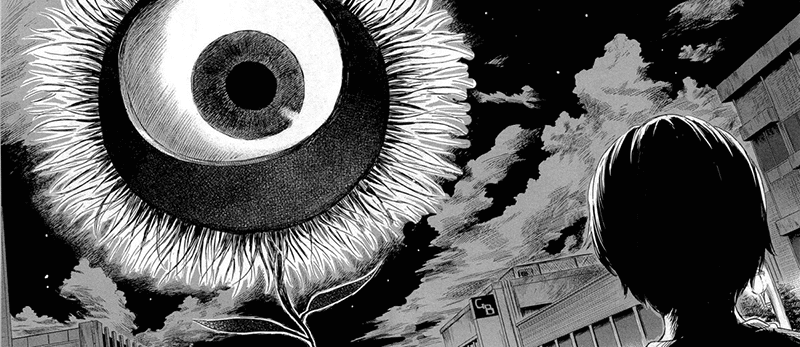

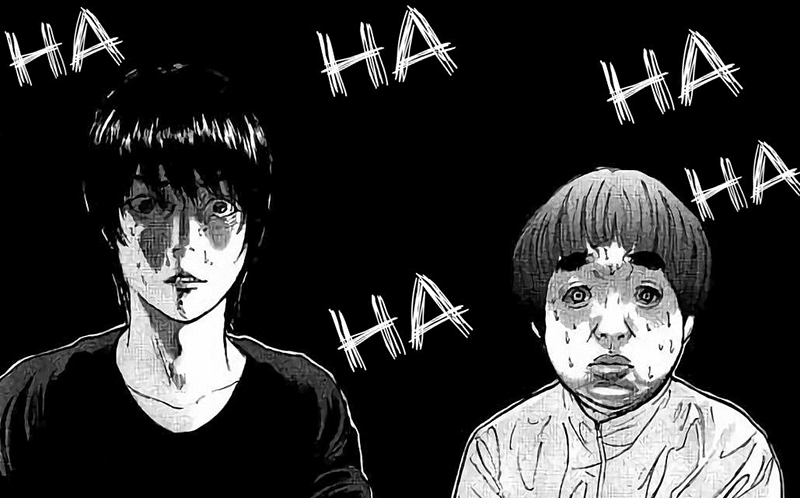

6. Nijigahara Holograph

Nijigahara Holograph is infamous for how hard it is to follow, but that reputation can distract from what it’s actually doing. The confusion isn’t a gimmick. Inio Asano builds a story where trauma and guilt are never resolved, and where time feels like a loop the characters can’t escape. If you’re looking for a depressing manga that treats damage as permanent, this is one of manga’s harshest portraits.

The manga revolves around a small-town incident that doesn’t stay in the past. A childhood act of cruelty becomes a quiet shadow that later lives revolve around, even when characters pretend they’ve moved on. Nijigahara Holograph doesn’t frame trauma as a single defining moment, either. It spreads outward, shaping friendships, relationships, self-image, and the ways people hurt others or themselves. That ripple effect makes the narrative feel so suffocating.

Asano’s structure reinforces the emotional logic. Scenes jump between years without warning, points of view blur, and cause and effect often arrive out of order. You’re asked to assemble a meaning from fragments, but the act of assembling never produces relief. Characters aren’t redeemed through understanding what happened. They’re trapped repeating behavior that feels inevitable, even when it’s ugly or self-defeating.

The content is also relentlessly dark. Abuse, sexual violence, murder, and other atrocities appear not as isolated shocks, but as part of a world steeped in cruelty. What makes it especially bleak is the ordinariness around it. The town looks ordinary. The people look normal. The art is precise and grounded, which makes the eruptions of ugliness land harder because nothing about the presentation signals distance or fantasy.

Nijigahara Holograph will alienate readers who want clear answers or tidy timelines. It’s closer to a psychological study than a conventional plot, and it’s easy to finish it feeling unsettled, but not fully understanding it. But if you can tolerate the ambiguity, and are open to rereading, the experience is devastating in a way few manga attempt. It’s a depressing manga about generational trauma as a lingering condition. The worst isn’t what happened, but how it influences those who survived it.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Mystery, Surreal

Status: Completed (Seinen)

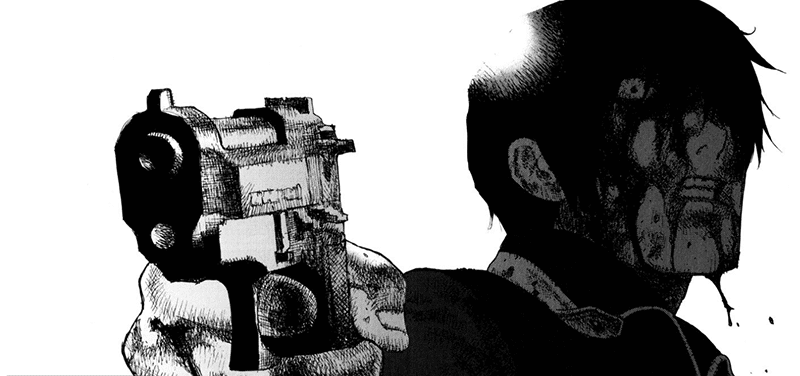

5. Freesia

Freesia isn’t depressing because it piles tragedy on top of tragedy. It’s depressing because it imagines a society that has legalized its worst instincts and then shows the psychological price for the people living in of it. Jiro Matsumoto frames the retaliation law as order, but it functions like a slow-acting poison. Once revenge becomes policy, violence stops being an exception and becomes institutional, and the people tasked with carrying it out rot along with the system.

The setup is deceptively simple. If someone is killed, the relatives or loved ones are granted the right to retaliate, either personally or through hired enforcers. Kano is part of that system, tracking down and killing people who’ve been designated as targets. It’s starts like a revenge thriller, but Matsumoto is after something uglier. The killings aren’t climactic payoffs. They’re administrative outcomes.

Kano’s perspective makes the entire world feel unstable. His hallucinations and delusions aren’t treated as stylish or dramatic twists. They’re presented as a constant condition that bleeds into everything until reality and disorientation become inseparable. The result is an unusually intimate depiction of mental illness, one that doesn’t offer the reader a safe, objective distance. You’re inside Kano’s head, forced to share his uncertainties.

What makes it hit harder is how little comfort anyone else provides. Nearly every character feels compromised, damaged, or numb. The law that’s supposed to balance loss multiplies it, pushing ordinary people into roles they won’t survive emotionally. Freesia’s normal ambiguity centers on that theme. Targets aren’t always monsters. Some are remorseful, some are pathetic, and some are products of the same society that doomed them. Yet none of that matters once your name is on the list. Guilt and innocence don’t matter. Procedure does.

Matsumoto’s bleakest insight is how this kind of work twists people over time. The retaliation enforcers aren’t stylized as antiheroes. They’re men whose sense of empathy has been burned away, sometimes violently. Mizoguchi is the perfect example. Now he’s a monstrous killer who loves hunting his targets and abuses his wife, he was once a loving husband. That contrast doesn’t redeem him. It shows how thoroughly the world has broken him.

The art matches the mood. Faces look worn down, streets feel claustrophobic, and the line between gritty realism and surreal hallucination is thin enough to blur at any moment. Sex and violence are depicted in ways that feel grotesque rather than exciting, reinforcing how dehumanized everyone has become.

Freesia stands out for how it explores societal decay through the inner collapse of its characters. It’s not a story about catharsis; it’s about a world that’s been stripped of all meaning.

Genres: Psychological, Crime, Drama

Status: Completed (Seinen)

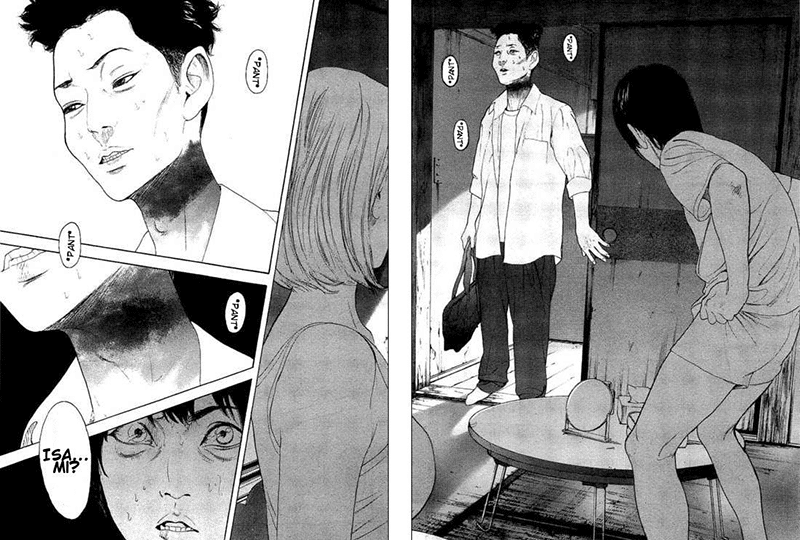

4. Bokutachi ga Yarimashita

Bokutachi ga Yarimashita is depressing in how it treats guilt not as a moment, but as a lifelong condition. Kaneshiro Muneyuki, best known for Blue Lock, wrote a story that’s far more intimate here. It’s a character study about ordinary teenagers who make one reckless choice, then discover that moving on doesn’t mean the weight disappears.

Tobio Masubuchi and his friends are entirely ordinary, drifting through high school and the rest of life with the same uncaring attitude. When one of them is humiliated by delinquents from another school, they decide on retaliation, more prank than crime. The point isn’t the scheme, but the moment it escalates. Once consequences arrive, the manga stops caring about excuses and documents the damage.

What follows is psychological erosion. Each character responds differently to the same guilt: denial, forced normalcy, impulsive self-destruction, or cold rationalization. None of it works. The longer they try to talk themselves out of responsibility, the more they spiral into panic, paranoia, and self-hatred. Bokutachi ga Yarimashita is a depressing manga because it understands how guilt shapes people, and how it becomes routine. It creeps into relationships, reshapes identity, and turns everyday moments into tests of whether you can live with it.

Kaneshiro’s writing stays close to the characters’ shame without turning it into melodrama. The tension often comes from what isn’t said or done: a laugh that’s a little too loud, a blank stare held too long, a conversation where everyone’s pretending they’re fine because admitting otherwise would shatter the illusion. The art supports that restraint. It isn’t flashy, but it’s sharp about body language, facial expressions, and the physical awkwardness of people trying to act normal while they’re unraveling.

The most punishing element is the lack of catharsis. This isn’t a redemption story, and it doesn’t offer emotional release. Even when life appears to stabilize, the story insists on a harsher truth: some wounds don’t heal, but become part of who you are. If you want a depressing manga about moral collapse and the aftermath of a single devastating choice, this one will linger long after you finish it.

Genres: Psychological, Crime, Drama

Status: Completed (Seinen)

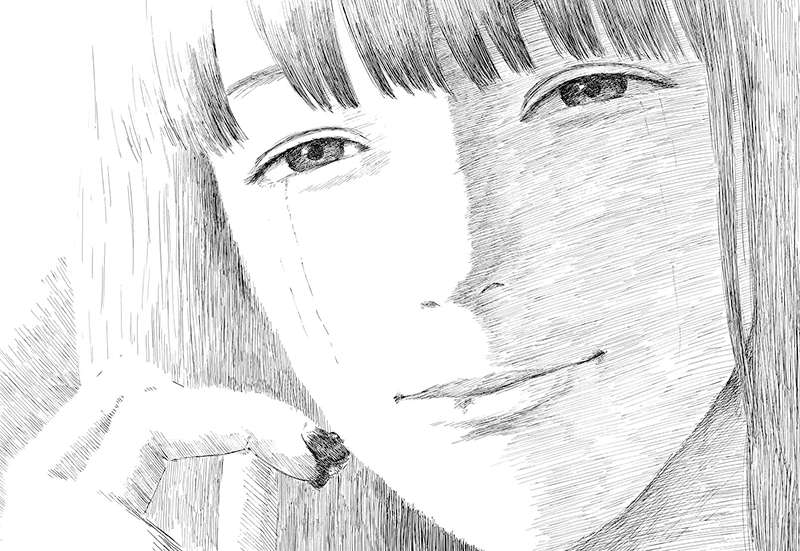

3. Helter Skelter

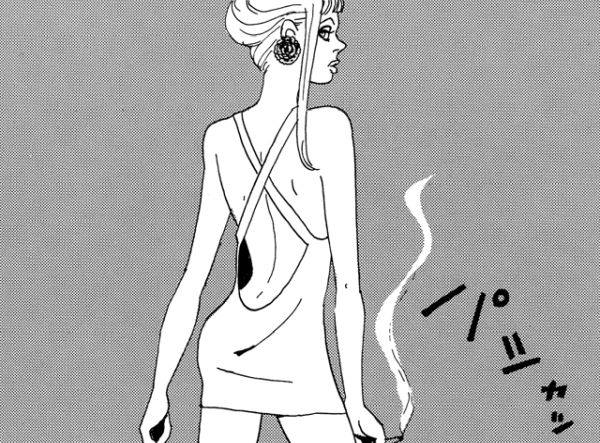

Helter Skelter is one of the bleakest portrayals of the entertainment industry in manga, treating fame as a machine that first manufactures a person, then disposes of them once they stop selling. Kyoko Okazaki builds the story around that theme, and the result is less a cautionary tale than an analysis of what happens when identity is reduced to image.

Liliko Hirokuma exists at the peak of celebrity perfection, but that perfection is engineered. Her body has been reconstructed through surgery, and her public persona is maintained through constant performances. The early tension doesn’t come from a single scandal or dramatic turning point. It comes from deterioration. As her body begins to fall apart and attention starts to drift elsewhere, the life she built becomes impossible to sustain. That’s where the manga’s depression lives, in the realization that she has no stable self to retreat to once the world turns away.

Liliko is written as both victim and predator, and Okazaki never asks you to simplify her into one or the other. She’s clearly been shaped by exploitation and obsession, then discarded the moment she’s deemed useless. At the same time, she responds by turning her fear outward. Her cruelty has an ugly logic. If she’s going down, she’ll take others with her. Watching her spiral is devastating because it isn’t framed as madness coming from nowhere. It’s a survival reflex inside a system that rewards self-erasure until it stops being profitable.

What makes Helter Skelter stand out among depressing manga is how wide the collateral damage feels. Liliko’s collapse isn’t contained within her own inner life. She drags other people down with her, whether through manipulation, jealousy, or the sheer pull of someone trying to remain the center of the world. The story offers no comfort, no moral cleansing, and no tidy resolution. It lands on the uglier truth that some people are broken by what they’re made to be, and they break others in return.

Okazaki’s art reinforces that instability. The linework is raw and uneasy, with expressions that feel slightly off even in quieter moments. It isn’t aiming for glamor, and that choice matters. The visuals keep reminding you that the polished surface is a lie, and that the body and mind underneath are coming apart. Helter Skelter is a depressing manga that’s unforgettable for how it captures vanity, addiction, and the horror of being consumed by your own image.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Avant-Garde

Status: Completed (Josei)

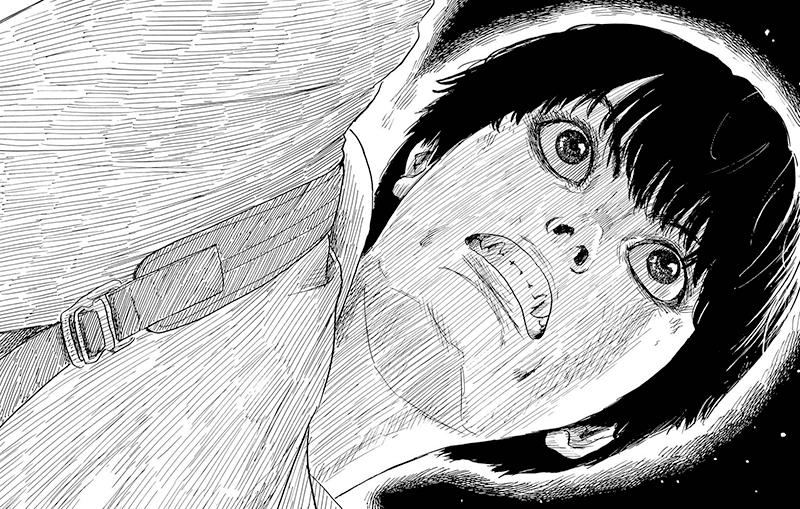

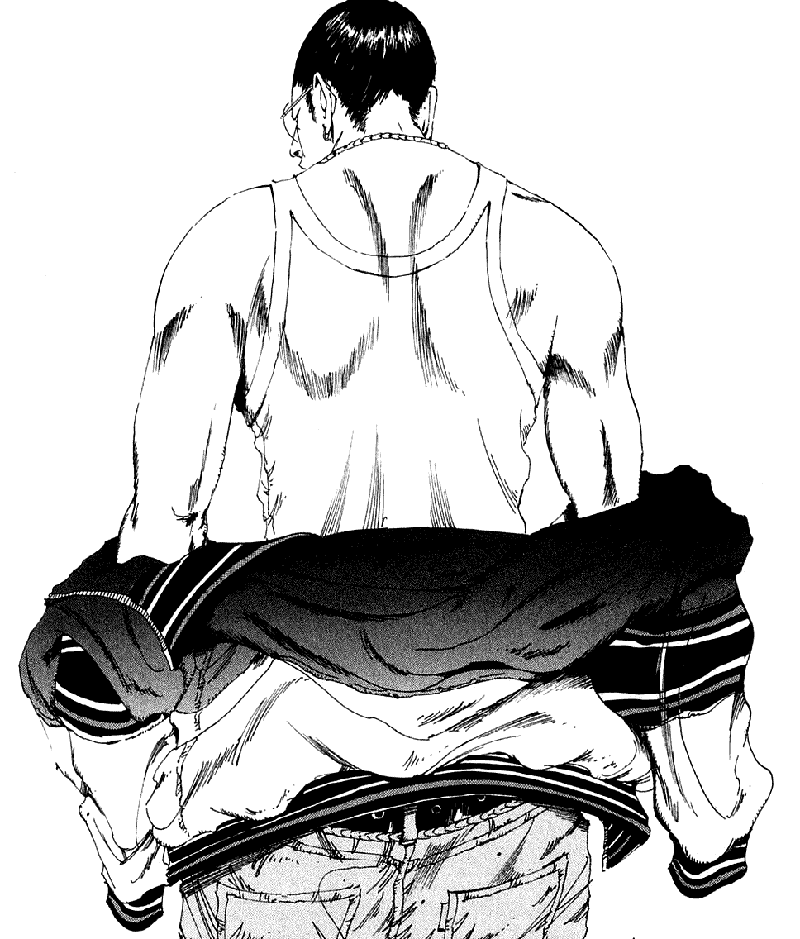

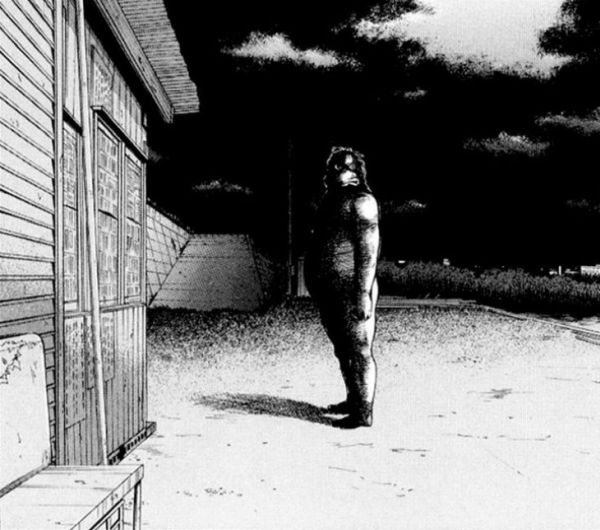

2. Himizu

Few manga commit to hopelessness as fully as Himizu. Minoru Furuya doesn’t treat despair as a dramatic spiral or a single breaking point. He presents it as a lived condition, a daily atmosphere that seeps into every thought, relationship, and decision. The result is a depressing manga in the most direct sense, not because of shock, but because it shows how misery can become routine.

Sumida’s goal is painfully modest. He doesn’t want greatness or escape, only a quiet, ordinary life with as little trouble as possible. Even that proves to be unattainable. He’s abandoned by his mother, trapped with an abusive alcoholic father, and left to grow up without stability, protection, or any adult safety net.

What makes Himizu hit so hard is how it captures the psychology of a person who feels spent. Sumida isn’t written as sympathetic, innocent, or purely a victim. He recognizes his own ugliness, but keeps repeating the same behavior anyway. The tension between self-awareness and powerlessness is where the manga’s depression takes shape. It’s not about a single traumatic event. It’s about what happens when a person believes nothing better is possible. The supporting cast reinforces the bleakness instead of offering relief.

The people around Sumida aren’t here to fix him or provide him with a path forward. They reflect different forms of the same problem: instability, denial, misplaced hope, and the kind of optimism that feels delusional when not even basic necessities are met. This never turns into melodrama. It stays cold, grim, and uncaring.

Furuya’s art is a major part of why the series feels so unpleasant, in the right way. Faces stretch and warp in moments of panic or humiliation, and the ugliness reads as emotional truth rather than stylistic noise. It’s a visual language that refuses comfort. Even when scenes are quiet, the expressions and body language suggest people are merely waiting for the next problem.

Himizu also denies the reader any form of release. There’s no breakthrough or happiness waiting at the end, no moral balance, and no sense that suffering produces wisdom. It’s a story about enduring, and sometimes failing to endure, with nothing guaranteed except the days continuing to tick by. If you want a depressing manga about alienation, self-hatred, and hopelessness, Himizu is one of the harshest examples in manga.

Genres: Psychological, Drama, Tragedy, Slice of Life

Status: Completed (Seinen)

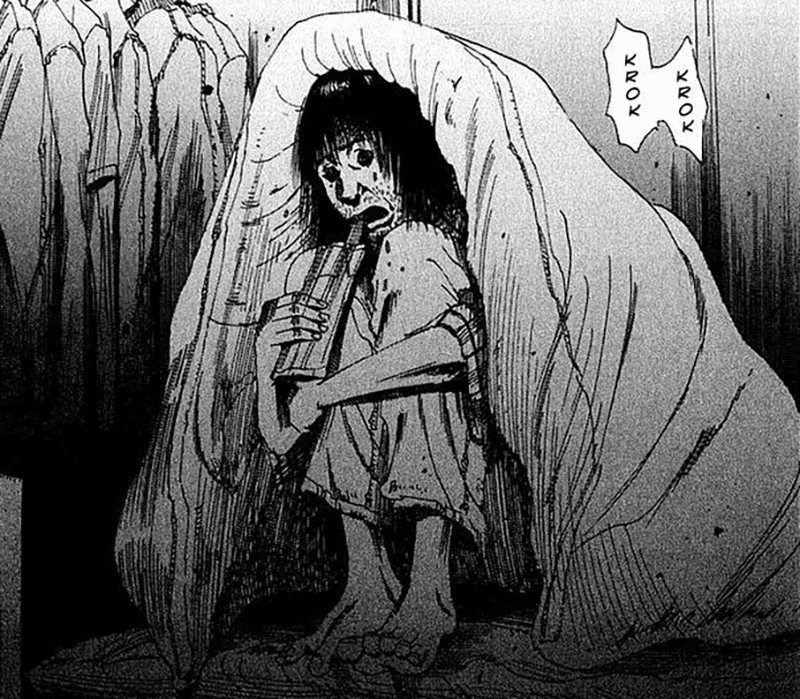

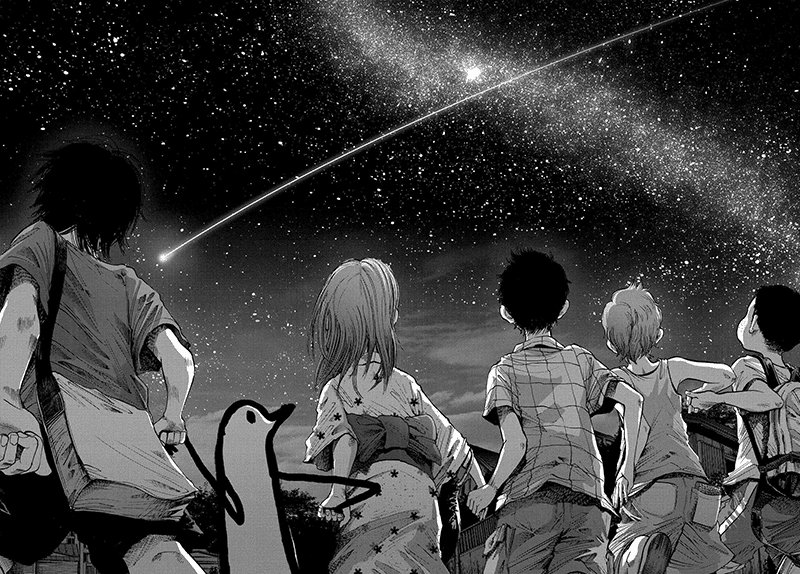

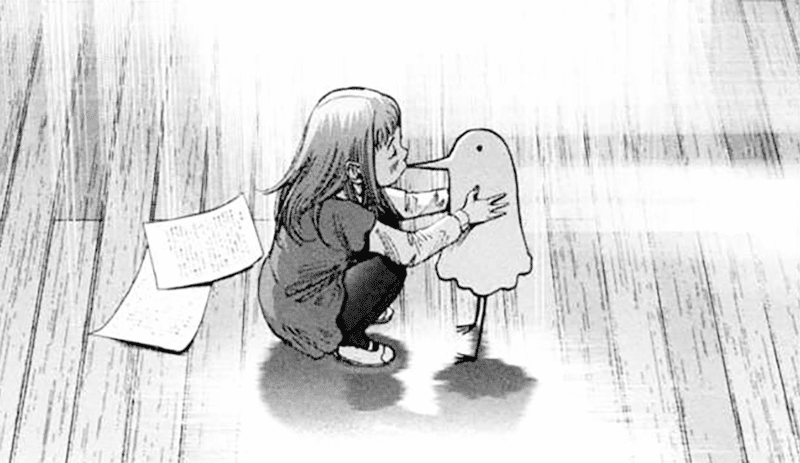

1. Oyasumi Punpun

By reputation, Oyasumi Punpun is impossible to ignore. It’s often cited as the most devastating depiction of emotional collapse in manga, and it isn’t built on cheap tragedy. Inio Asano’s approach is slower, harsher, and more personal. This is a depressing manga where life doesn’t break in one moment, but erodes through neglect, shame, and the long aftermath of formative damage.

Punpun Onodera enters the story as an ordinary child with small hopes. That ordinariness matters because the manga never frames him as exceptional. Asano focuses on the mundane sources of ruin: a home defined by instability, adults who can’t protect anyone because they barely function, and relationships that offer comfort one moment and harm the next.

The early setup is understated, but the accumulation is relentless. Oyasumi Punpun isn’t about shocking events. It’s about drifting through life, and the tiny, quietly devastating moments that stack up until they consume you.

Asano’s most striking choice is visual. The environments are rendered with intense realism, down to cramped rooms and harsh urban details, while Punpun and his family appear as simplified, bird-like figures. It creates distance without making the emotions abstract. Punpun looks out of place in his own life, and that dissonance becomes the series’ quiet core.

The emotional weight comes from how unromantic the series feels. Depression isn’t a mood, and it isn’t a single traumatic wound. It’s guilt, desire that turns obsessive, and self-loathing that becomes normalcy. Many of the relationships are intimate in a way that feels dangerous, manipulative, and shaped by dependency, or the need to be saved by someone who themselves needs saving. Asano doesn’t offer moral clarity. People might be sympathetic and damaging in the same scene, and this ambiguity makes the story feel so real.

The final arc grows louder and more chaotic, and the escalation feels melodramatic compared to the earlier, quieter suffocation. For me, it works, but not consistently. When depression and self-hatred stop being internal, they become volatile, sometimes violent, and rarely reversible.

Oyasumi Punpun succeeds in showing the most intimate kind of darkness, the kind that doesn’t rely on spectacle to hurt. It’s less about sadness than the gradual loss of identity and the unsettling fact that life keeps going.

Genres: Psychological, Drama

Status: Completed (Seinen)